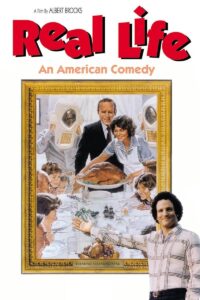

Somewhere between PBS’ An American Family and E! network’s Keeping Up With the Kardashians there emerged a widespread interest in observing the private mechanics of the nuclear family, and when that became tired, we were left with endless spinoffs and remarketing to redirect our time from our own families. But before anyone had the chance to be shocked that the housewives of Anytown may not be as real as they claim, filmmaker and comedian Albert Brooks took to uncovering the production behind the production in his 1973 faux-documentary production Real Life—the next step in reality television, the opening title prepares its audience.

While the television genre may be called “reality,” it’s well understood by now that entertainment does not come from the mundanity of the human experience like it does from the manipulation of money-grubbing producers—the camera and investors just don’t appreciate tedious routine as much as they do catfights. And entertainment, of course, is what Brooks, playing a more immoral, narcissistic version of himself, struggles to fabricate when he’s given the opportunity to film an Arizona family.

But the concept is groundbreaking, we’re informed early on: Brooks has attempted not only to document the life of a real family but also the people who came to film them and how they influence one another. With access to the sophisticated resources of the National Institute of Human Behavior, Brooks reveals, thousands of interested potential American families were whittled down to the Yeager family, a four-person household made up of a veterinarian father (Charles Grodin), a weary mother (Frances Lee McCain), and two whiny children (Lisa Urette and Robert Stirrat). As far as Brooks understands, he’s a shoo-in for an Oscar, and even a Nobel Prize.

Unfortunately, the father comes off as unsympathetic and is later filmed accidentally killing a horse while performing its surgery. And the children aren’t getting the screen time they’d like. And the mother isn’t having it. And all hope is lost. As one would suspect, the production does not turn out, and Brooks falls further into egomaniacal madness.

Real Life has, most of all, its deadpan humour to thank for its success, as the film may not have the most developed characters or the strongest pacing. But in its language of small glances at cameras and unnatural behaviour, there could be nothing funnier. Bulbous helmet-like cameras worn on the heads of the fictional cameramen pop in and out of frame in an almost perpetual jump scare. It is a wonder the family even got to day 52.

Brooks reimagines quantum mechanics by offering the observer effect as an American satire; as he and Werner Heisenberg understand, no reality can exist in front of a cameraman. And he acts as a time traveller to a 1970s audience unknowing of what their TVs may be stuffed with in 50 years time. Although no Oscar or Nobel Prize was achieved, Brooks’ brilliance behind and on screen is an accurate depiction of real-life fake life.