It’s common knowledge among my peers by now that horror is, generally speaking, the genre I least admire. That’s not to say I don’t like creepers and crawlers—I most certainly do—however, it’s for a variety of reasons, beginning with tasteless shock and ending with the perpetual fear I already experience as a young lady, that I steer away from the genre.

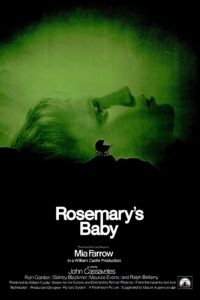

That’s, I figure, where writer Ira Levin enters, composing horror stories where fright is not only possible in the underworld, but evident in the world we knowingly exist within. Later produced into motion pictures, Rosemary’s Baby (1968), directed by Roman Polanski, and The Stepford Wives (1975), directed by Bryan Forbes, are two of those stories.

We meet Rosemary’s Baby where many of the greats tend to come from: New York City, specifically in an NYC apartment where Rosemary (Mia Farrow) and her actor husband Guy (John Cassavetes) are looking to rent. Finding one that suits their lifestyle—wishing to conceive children—they move in within a few days despite rumours of the previous tenant’s odd behaviour. Odd behaviour is displayed by just about everyone belonging to the Bramford apartment, including the Castevets, an elderly couple known for their hospitable and idiosyncratic personalities. Odd not in the manner neighbours always are, but a sinister, uncanny manner that Satanists may be. Oddity which manifests in Rosemary’s pregnant belly as sharp pains begin to develop.

Do not mistake this: Rosemary’s Baby is not about the occult, although it does disguise itself as so. Rosemary is forced into insanity, through manipulation, through abuse, and through control, and that is where the story lies, in the belly of women’s oppression.

When Rosemary expresses her concerns of both her body and her neighbours, it’s brushed off as paranoia, and when she discovers the truth—that her baby is indeed the spawn of the Devil and is told she must care for it—she is exploited for her maternal instinct. Rosemary’s Baby is a retelling of millions of women’s experiences, done up in a Vidal Sassoon ’do and expressed through Farrow’s dazzling performance of women’s lib.

The Stepford Wives imitates this theme seven years later in the heart of small-town America. It follows a similar form, too: husband and wife move into a new home and find strange neighbours, although in the case of Stepford Wives, Joanna Eberhart (Katharine Ross) is the wife, Walter (Peter Masterson) is the husband, and they have moved to Stepford, Connecticut, where the women are ultra-polished housewives.

What makes Stepford Wives so frightening is the blatancy with which all malice is manufactured. The evil that traps and controls women is not well-hidden.

It was 1972 when the novel was published, and although housewifery is no longer the standard feminine work, and robots have not replaced women, as the story portrays, the final scene still stands as a marker for how we function under patriarchal constraints, sedated and emptied.

And I cannot think of anything scarier than that.