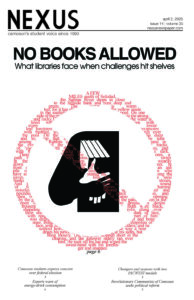

When it comes to distribution of books, there’s always a question of propriety and the follow-up of censorship. The subsequent challenging, shadow banning, or outright banning of books is most common in school libraries and curriculum-required books for students of high-school age and younger. This problem is most heavily documented south of the border in the United States—Texas and Florida banning the most, according to 2022 statistics. A question then presents itself to scholars, authors, and teachers north of the border as the challenges to books on library and school shelves begin to rise: could this, if not already, then begin to occur in Canada?

Confronting book bans always comes with a debate regarding censorship, as pulling books from shelves is itself a form of omission. The act of restricting or removing access to books containing subject matter considered offensive, damaging, or inappropriate for consumption leads to a precedent for future censorship of greater lengths and standards becoming deeply restrictive to the modes of education available.

This sentiment is echoed by Camosun College English instructor Kari Jones.

“If we’re not reading… teaching… or making those books available to children then… we’re not showing them history as it happened,” says Jones.

Camosun English instructor Janice Neimann argues it is “unethical” to omit historical reading. In fact, literary classics like To Kill a Mockingbird, Of Mice and Men, and Lord of the Flies have all been pulled from curriculums in schools for outdated and racist language used within them. Jones points out that there’s a genuine fear, mostly on the part of concerned parents who are sending in the book challenges in the first place, of the presentations of timely hate and racism being passed on to readers. Unfortunately, if the portrayal of racism in books, either intentional or a product of the time they were written, is prohibited from being displayed in school curriculum and libraries, less justifiable reasons for censorship may begin to creep into policies.

If portrayals of historical racism like in the classics, or bullying like in Diary of a Wimpy Kid, is inappropriate, then pieces written from the perspective of those experiencing that pain get banned, then any mention of race or childhood cruelty is banned, and so on until there are only sanitized portrayals remaining on the shelves.

Neimann says there’s misguided rhetoric of “safe spaces” as places where it’s expected, even required, for the environment to avoid discomfort. That discomfort, Neimann argues, is in fact critical to the learning process, and circles back to the subject of books: the context of uncomfortable subjects and portrayals in their pages further facilitates enriched education, doing that history justice.

The slippery slope of censorship thus brings us to the concerning habit of books portraying queer and BIPOC experience being challenged. Children’s book authors Danny Ramadan and Robin Stevenson had their books shadow banned by a Catholic school board in Ontario; Jones is a friend of Stevenson’s, and says that 12 of Stevenson’s books are being deliberated over by the Supreme Court of the United States. And with this begins a trend: the Canadian Library Book Challenges Data has reported a 55 percent uptick in challenges to books between 2022 and 2023, particularly with race, gender, and sexuality present in its subject matter. The challenges suggest an impression that the subjects of queerness and non-white perspectives are considered “inappropriate” for children to engage with or witness openly. It sends a message to authors, librarians, and young readers that such content is in some way shameful and unwelcome, which does not inspire the confidence to further learn about those experiences, even in cases where the book is still available through special request and permission from a teacher.

The Waterloo Catholic District School Board highlights particularly a dissonance of understanding by its Ontario Library Association representative, justifying the shadow ban by stating that the books are technically still available, just placed in a shelf only accessible to teachers. Though not direct erasure, how are children even meant to know the books are available to begin with, never mind the courage and resilience expected of a child in such a school to request a book on the matter when it had been made abundantly clear by the board that it is meant to be secretive?

Neimann pushes forward the concern of these targeted bans and challenges being an effort to control the education of children in rather exclusionary ways and by abusing the demeaning assumption that children are deeply fragile beings with little ability for critical thinking as justification for larger censorship. Jones, herself an author of books targeted towards children, acknowledges the concern of age appropriateness being relatively subjective, but says that trust and responsibility should be given to librarians and educators to give appropriate context and discernment, as opposed to concerned parents challenging material in reactionary ways. Neimann says that beyond schools and their libraries, those in lower socio-economic groups who may not have the means to gain their education and knowledge outside of public libraries are particularly affected by the push of book banning. And the system benefits from this demographic’s oppression of knowledge to remain dominant.

It’s worth noting an important distinction in this discussion: many of the concerns brought up in this discussion begin with the drastic images of empty school shelves and mass censorship of anything even tangentially related to race or queerness. It’s a harrowing sight to be sure, although the process in Canadian schools and libraries function much differently.

Jones mentions a union of sorts among Canadian libraries called the Library Learning Commons (LLC) that works out of BC. LLC is a fierce advocate for the freedom to read, and has a position statement that holds them to the fight for diversity in books featured in libraries and schools.

Libraries and schools in Canada are distinct from the US in their independent funding and internal processes on the collections they keep. People can and have sent in many challenges to books and requests to remove books from shelves, but it’s up to the deliberation and advisory of the librarians and the consultation of their peers to assess the need to relocate or remove books.

There’s little a complaining party can do about a book still being on the shelves when librarians have repeatedly concluded it has earned its place on the shelf. Of course, there’s still the risk of retaliation, groups pressuring their providers to cut or reduce funding to the libraries in order to enforce their demand. Schools and libraries with an insufficient amount of funding for full-time librarians, says Neimann, are particularly vulnerable to this tactic of book suppression.

There are, however, counter-measures librarians and readers can partake in to continue the preservation of such literature. Crucially, supporting local libraries. Whether that be through fundraising to allow skilled staff and large collections to be acquired, or reading and borrowing books from them, the public’s presence and continued borrowing of books matters and signals to the libraries that such books are popular enough to be kept for future readers in regular rotation.

But if you have the money, as books are increasingly more expensive, it would also be wise to acquire banned and shadow-banned books so that at the very least our own personal libraries are populated with the books in case they are taken away. Neimann emphasizes preserving physical media in particular; while the internet is accessible, it is dependent on servers staying up, access to Wi-Fi, and, naturally, access to electricity.

Jones suggests The Canadian Library Challenges Database as being a prime source for lists of various challenged books along with the reasoning behind their challenges. Places that sell second-hand books of all kinds are great places to look. One option in Victoria is Camas Books & Infoshop on Quadra Street, which has a selection of banned books at lower prices.

Reading is key, but so is the community voice. Citing the Cite Black Women Collective, Neimann emphasized the sharing, assignment, and understanding of challenged and banned books as being equally as important as reading them yourself.

The Freedom to Read Week, an annual event encouraging Canadians to reassert and defend their intellectual freedom, brings many inflammatory literature out of the woodwork at bookstores and libraries, occasionally with little written pieces explaining why the books are controversial to begin with. It is a form of scholarly appreciation that allows you to draw your own conclusions on the work, and take in the literature so many seem to want erased.

Neimann emphasizes media literacy; without it, context and nuances of stories, especially controversial ones, are lost, and the abandonment of that knowledge contained in the books follows. There’s no true value in reading banned books without a skill in media literacy, and it is a muscle that must be sculpted and worked on a regular basis. It may seem a chore, but it’s essential for all consumption of every media type, books especially.

Go forth and read, folks. Learning is itself a form of resistance.