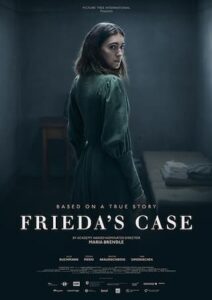

Frieda’s Case

Frieda’s Case depicts the real-life 1904 Swiss court case of Frieda Keller, a woman charged with the murder of her five-year-old son, Ernst.

Unlike a more typical legal drama, the actions of Frieda are never in question—she confesses within the first few minutes of screen time. Yet, despite believing her confession, her family and co-workers are surprisingly defensive of Frieda’s overall moral character. Central to the story is uncovering and evaluating what ultimately motivated Frieda to commit such a horrific act.

Much of the viewing experience hinges on the trickling in of various important details that I won’t spoil here. This is a triggering movie in regard to the topics of child death and sexual assault, which is depicted in detail. For those not suffering from such traumas, the movie is useful in broadening an understanding of women’s rights through Frieda. The costuming and set pieces are immaculate and on par with other, higher-budget period releases this year.

Admittedly, by the third act, I did start to tire of listening to the paternalistic tirades, mostly delivered by prosecuting attorney and main investigator Walter Gmür, who often has the unfortunate effect of shutting down key figures in the case. This frustration is likely intentional on the part of filmmaker Maria Brendle. But the movie is rhetorically at its strongest when Walter’s disdain for Frieda feels somewhat understandable, as his voicing of these assertions forces the audience to evaluate their own assumptions. When his statements don’t feel justified, the experience borders on the tedium of listening to an irate uncle at Thanksgiving.

Brendle also makes the conscious decision to preserve Ernst’s humanity, mostly in the form of flashback sequences. The inner armchair director in me would have liked these sequences to be used more sparingly. Admittedly, at some point during the viewing experience, I became completely desensitized to images of little Ernst being the undoubtedly adorable little five-year-old that he was.

Tragedies such as these are at their most emotionally satisfying in catharsis. Guts should be wrenched and tears jerked but, tellingly, there were no sniffles heard from the audience.

That said, this movie succeeds as a depiction of history. While certain issues addressed in the movie are specific to Switzerland in 1904, others are not. Contemporaneously, there are those who, to varying degrees of success, argue to roll back the social progress of the past hundred years, in favour of a supposedly simpler, pre-feminist time where men were men and women were… you get the point. 1904 was that time, and, as this movie reminds us all, it sucked.

Sweet Summer Pow Wow

In Writing the Romantic Comedy, author Billy Mernit argues that rom-coms are possibly the most difficult genre to attempt. According to Merrit, apart from needing to be funny—no small feat—rom-coms are quintessentially about flawed people achieving completion via the power of love.

I argue here that more difficult still is the teen rom-com. This is because the genre preserves all the demands of its adult counterpart while adding the challenge of needing to appeal to teens (or, let’s face it, tweens) and their parents. Teens may enjoy themes of freedom and rebellion but parents naturally prefer obedience and good role models. This movie falls more on the latter side of this continuum.

Sweet Summer Pow Wow is about 17 year olds Jinny and Riley; Jinny is touring as an owl dancer the summer before she is set for university. Jinny is unsure the direction of her life while Riley lives at home with his abusive, alcoholic father and dreams of a better future. Jinny’s mother, Cara, is eager to see her daughter follow the narrow path of success she herself was never encouraged to pursue. Needless to say, Cara does not approve of Riley, whom she sees as a needless distraction and potential life-ruiner, leaving Jinny torn between her love for Riley and wanting to please her mother.

The setup may lead one to intuit that Jinny will assert herself to her mother, Riley will overcome his trauma, and Cara will loosen up. Sweet Summer Pow Wow sticks to the landing on the first two points.

Jinny begins the movie already asserting herself and communicating her wants. Despite her complaints, Jinny remains extremely obedient throughout. Riley, while understandably sensitive about his home life, never has this sensitivity manifest in any particularly unappealing actions. In many ways, Riley is the perfect boyfriend, taking Jinny on lavish dates and telling her that it’s okay to cry. Much of the character development is done by Cara, who is, admittedly, still fun to watch.

The ultimate question is whether or not Sweet Summer Pow Wow is worth watching. The answer depends entirely on your affinity for the rom-com genre as a whole.

This movie is definitely better than most of the two-bit schlock coming out on Netflix these days. The comedic elements are also genuinely funny. And while Canadian cinema has been shamefully lacking in terms of Indigenous representation, this movie is an enjoyable way to see Indigeneity depicted on screen.