Why has society so viciously disadvantaged women? It shouldn’t be a skill-testing question: the answer is patriarchy.

Patriarchy is a social system in which men hold primary power and authority in political, social, and economic spheres. It’s not limited to individual relationships—it extends to societal structures, cultural norms, and legal systems that perpetuate male dominance and female subordination.

Across cultures, societies, and historical periods, patriarchy has manifested in various forms. It’s deeply ingrained in many institutions, such as family structures, religious practices, education systems, and the workplace. It can have both overt and subtle mechanisms, with the overt being laws, policies, and practices that explicitly privilege men over women. Subtler manifestations of patriarchy include gendered social expectations, stereotypes, and values that dictate how individuals should behave based on their gender.

The impact of patriarchy on women is profound and wide-ranging. There lacks perspectives from diverse genders, BIPOC, and other minority groups in Parliament and our legislatures. Patriarchy often reinforces harmful stereotypes that limit and control people’s choices and opportunities. Oppression by the patriarchy and misogyny continue to be focuses of feminism today.

Barbie sparked numerous debates on social media when it came out due to its feminist and anti-patriarchal themes. The best example I’ve heard lately that describes the struggle women face under patriarchy comes from the movie, when character Gloria tries to console Stereotypical Barbie.

“It is literally impossible to be a woman,” she says. “We have to always be extraordinary but somehow, we’re always doing it wrong… You have to be a boss, but you can’t be mean. You have to lead but you can’t squash other people’s ideas.”

Another double standard that Gloria mentions is motherhood. A woman’s right to choose how she lives her life is part of the package of feminism. That includes the choice to be a mother. The perception that women must be the caregivers is a subtle patriarchal gender stereotype; there are men with the capacity to be caregivers.

“You’re supposed to love being a mother but don’t talk about your kids all the damn time. You have to be a career woman but also always be looking out for other people.”—Gloria

Then there’s something I really can’t stand in the patriarchal hellscape—getting scapegoated for men’s behaviour. For example, dress codes that force women to cover up because men can’t control themselves. The argument that women showing skin are distracting is a fallacy. Let’s be real: women are still accused of being a distraction when clothed.

“You have to answer for men’s bad behaviour, which is insane, but if you point that out, you’re accused of complaining. You’re supposed to be pretty for men but not so pretty that you tempt them too much or threaten other women.”—Gloria

It’s truly exhausting—nothing is ever “good enough” when you’re a woman but the same things would be acceptable for a man. The playing field isn’t level, and the goalposts seem to keep moving.

“It’s too hard, it’s too contradictory and nobody gives you a medal or says thank you, and it turns out, in fact, that not only are you doing everything wrong but also everything is your fault.”—Gloria

Patriarchy harms men, as well. By enforcing restrictive and rigid gender roles, patriarchy pressures men to conform to ideals of toughness, competitiveness, and emotional stoicism. This can have detrimental effects on men’s mental health, relationships, and overall well-being. Patriarchy discourages men from expressing vulnerability or engaging in emotionally supportive relationships, reinforcing harmful stereotypes about masculinity.

We now suffer hypermasculinity, which is characterized by an extreme or exaggerated form of traditional masculinity and misogyny.

“Your body, my choice” follows this philosophy proudly and is becoming more ubiquitous. If overturning Roe v Wade wasn’t enough in the US, the culture has followed.

Until patriarchy is dismantled, hypermasculinity and misogyny will exist and, therefore, the feminist movement will continue to be a necessity; they’re all interconnected.

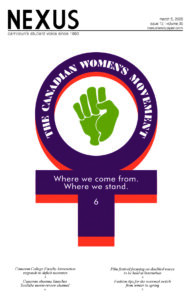

Generally, when people talk about the women’s movement, they refer to 1970s feminism; however, that’s the second wave of feminism. The women’s movement started long before that.

The first notable stand for women’s rights was in 1405 when Italian Christine de Pizan wrote The Book of the City of the Ladies, a book about women’s position in society. This was in response to books written by men about the faults of women and questions regarding their humanity. At that time, most women couldn’t read or write.

During the French Revolution, working women fought for equality by holding demonstrations and marching to Versailles. Unfortunately, their efforts did not lead to change. Due to France continuing with the status quo, Olympe de Gouges wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen. De Gouges was responding to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and wanted to expose the French Revolution’s failure to achieve gender equality. Consequently, de Gouges was accused of treason, tried, convicted, and immediately executed.

Feminism’s first wave began at the end of the 19th century and is commonly known as women’s suffrage. This was a time of mass demonstrations, publishing papers, organizing debates, and establishing international women’s organizations.

In Canada, the ability for all women getting the right to vote in both provincial and federal elections took several decades.

Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta were the first provinces to grant women the right to vote in their elections in 1916, with British Columbia and Ontario giving women the right to vote the following year.

In 1917, the War Time Elections Act was passed in Canada; with it, women with male relatives fighting in World War I and women in the military were given the right to vote in federal elections. All Caucasian women were able to vote in federal elections in 1918; however, minorities were still denied the right to vote.

It wasn’t until 1940 that Quebec, the final province to hold out, gave women the right to vote; the final territory to grant women the right to vote was the Northwest Territories in 1951. (Indigenous women and men were only allowed to vote starting in 1960.)

Despite getting the right to vote in Canada, women were not legally considered “persons” under the British North American Act. That began to change in 1916 after a group of women were removed from a court room during a prostitution case. The reasoning for the removal was that the testimony wasn’t fit for “mixed company.”

Emily Murphy, a well-known women’s activist in Alberta, challenged that decision by saying if it was not fit for “mixed company” the trial should be conducted by a woman. Alberta attorney general Charles Wilson Cross agreed and appointed Murphy as a judge. However, a lawyer involved in the case disagreed and challenged her ability to preside over the case since she wasn’t a “person.”

The issue went to the Supreme Court of Alberta, where the courts ruled that women were, in fact, “persons.” But Murphy didn’t stop there. She decided to test whether women were “persons” on a federal level by putting her name forward to be a senator. The answer was no. With almost 500,000 signatures on a petition to have Murphy appointed, prime minister Robert Borden said he would appoint Murphy if he could, but a British common-law ruling that became the basis of the British North American Act stated that “women were eligible for pains and penalties, but not rights and privileges.”

Murphy decided to join forces with Irene Marryat Parlby, Nellie Mooney McClung, Louise Crummy McKinney, and Henrietta Muir Edwards, who became known as The Famous Five, to fight the decision and have women recognized as persons under the law.

Finally, after several long, arduous trials, women were finally declared persons on October 18, 1929.

The second wave of feminism didn’t start until 1963, with the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, and ended in the early-to-mid 1980s, with focus on peace and nuclear disarmament, equality in education, employment and pay, and violence against women.

It was during the second wave when the Voice of Women (VOW) was founded to fight the use of nuclear weapons as the Cold War and Vietnam War were happening. As the world watched the Berlin Wall being built and felt the intensity of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Canada accepted the use of Bomarc missiles, which had nuclear warhead potential. By 1963, Canada signed a partial ban on nuclear testing.

Representation of women grew in other media such as music festivals, theatre, and print. The National Film Board of Canada gave feminist performers such as k.d. lang opportunities with their Studio D venue. More feminist playwrights filled the theatres with their works and over 50 feminist magazines and newspapers popped up across Canada next to mainstream women’s magazines.

To gain employment equality and break free from the confines of only clerical work, health care, and teaching, feminists fought for a complete education overhaul, from elementary to university. Women in unions across Canada fought for pay equality by striking despite making up only 32.3 percent of all unionists in the country.

During the second wave, feminism in Canada reached a level of visibility that surpassed suffrage. A coalition of over 30 women’s groups fought for and won a federal Royal Commission on the Status of Women, which made recommendations on equal pay for equal work of equal value, maternity leave, daycare, birth control and abortion, family-law reform, and revision of the Indian Act.

The third wave of feminism—post-feminism—occurred in the 1990s and brought into focus intersectionality and racial issues, both nationally and internationally, equality in job opportunities and pay, and bodily autonomy. Pro-choice advocates also began fighting for women’s right to choose how to live their lives.

During this time, feminists began using pop culture to get their points across. The Riot Grrrl movement played a key role in this.

During this time, feminists began using pop culture to get their points across with fanzines filled with women’s stories of lived experiences of domestic abuse, eating disorders, discrimination, homophobia, racism, and more.

Music was also used as a medium to get the message across, with the Riot Grrrl movement, which started in Olympia, Washington, playing a pivotal role. Carving out a cultural space for women was one of the goals of the movement, with the three Rs representing the growl of the angry punk feminist.

In the Riot Grrrl Manifesto, their feminist values are clear: “Because we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak.”

The manifesto has a total of 16 statements in it, one of which sums up the entirety of the movement.

“Because we are interested in creating non-hierarchical ways of being and making music, friends, and scenes based on communication + understanding, instead of competition + good/bad categorizations.”

They explain the reason for using fanzines and music in their manifesto as well.

“Because doing/reading/seeing/hearing cool things that validate and challenge us can help us gain the strength and sense of community that we need in order to figure out how bullshit like racism, able-bodieism, ageism, speciesism, classism, thinism, sexism, antisemitism and heterosexism figures in our own lives.”

The movement set the stage for future female artists to have a voice about issues that mattered to them.

For decades, and even during post-feminism, women were fighting for equality in the workplace; however, not all women wanted to work outside of the home. The point pro-choice advocates tried to make (and are still trying to make) was that if women can choose bodily autonomy, they can make other choices that either adhere to traditional female stereotypes or avoid them.

There’s nothing wrong with choosing to be a traditional housewife over having a career, if that’s a woman’s decision. Parents spending time with their kids is a good thing. On the other hand, women having careers and breaking glass ceilings is also a positive. Does society need all women to have careers? No, society needs everyone to be happy and satisfied with their lives, whatever that looks like.

In 1996, women’s right to go topless was brought to the forefront. Ontario’s Gwen Jacob walked around in public then sat on her porch topless and got charged with indecent exposure under the Criminal Code (R. v Jacob (1996)). She stated that she was trying to bring awareness to the double standard of men being able to go shirtless but not women. Her argument was that breasts were just fatty tissue. The judge, however, took the position that breasts were sexually enticing both by sight and touch. Jacob was fined $75.

Jacob wasn’t finished with her quest to expose the hypocrisy; she appealed the decision. The Ontario Court of Appeal acquitted her case, stating it is not a sexual act or indecent to be topless. Surprisingly, the Ontario government opted not to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC); instead, they accepted the verdict.

By not appealing to the SCC, the decision did not become automatically binding on other provinces. However, in most provinces there has been a case in which the decision has been upheld and the right for women to be topless in that province exists. BC is one of those provinces.

Even though women have the right, it’s still contentious. I’ve been at the beach multiple times where women who I’d guess were in their 20s were topless and women 20 to 30 years older got upset about it; some even asked the girls to cover up. Unfortunately, we’re still a prudish nation.

R. v Jacob was also used in the courts to challenge and win the right to breastfeed in public. In my experience, whenever someone took issue with me breastfeeding my baby in public, they claimed it was “indecent” to expose my breast in public. Legally? No. Morally? Depends on who you ask; we’re not all prudes.

So where does that leave feminism today? Well, we’re in the cyberfeminism/networked feminism fourth wave. Major focuses in cyberfeminism are body positivity, sexism, misogyny, and gender-based violence against women.

One of the most notable moments so far has been the #MeToo movement, which originally began in 2006 when the phrase “me too” was coined by Tarana Burke on Myspace to help survivors of sexual assault and abuse feel less alone. The movement gained attention in 2017 when actress Alyssa Milano posted on Twitter using the hashtag #MeToo.

After Milano tweeted, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Lawrence, Uma Thurman, Ashley Judd, and others, particularly in Hollywood, started sharing stories of sexual harassment and abuse. Media coverage of the movement spread quickly and sent shockwaves through Hollywood, causing high-profile terminations.

Millions of people started sharing their stories shortly after it hit mainstream media. As awareness grew, #MeToo started being used around the world.

One day I made the mistake of trying to watch the hashtag through a program with automated refresh every second. The stream of tweets moved so fast that my eyes couldn’t focus; when I stopped it to read the stories it was heartbreaking.

With all the countless stories shared, did #MeToo accomplish anything? Short answer: yes. Across Canada, crisis centres saw an increase in calls from survivors, police received more reports of sexual assault, and workplace policies regarding sexual harassment were reviewed. In the 2018 federal budget, investments were made into employment equality and programs to fight gender-based violence and promote gender equality.

The steps are in motion. Progress has indeed been made. As a nation, and globally, we have seen growing response and policy driven through the feminist movement.

The path has been forged for us to continue to enact on issues that we still face today. Not only for women, for everyone. We all benefit from following through with the collective promise of equality.