“Kill everyone now. Condone first-degree murder. Advocate cannibalism. Eat shit. Filth is my politics, filth is my life.”

Should one try to vindicate Pink Flamingos (1972) from its vile cruelty to all which is good, they may fall flat. But should they instead embrace its vile cruelty, welcome its offenses, and affirm their own derangements, they may find themselves vindicated and the film therapeutic—as it is, more than a film, medicinal.

There is a crowd for it. Whatever “it” is—filth, trash, shock. They watched it in grindhouse theatres, and when those were replaced with booming Cineplexes, they moved to the privacy of Pirate Bay for their fix. Mostly it features gore, nudity, and harsh language. But, sometimes, when the crowd is lucky, when they’ve already done enough damage, they also get something with real heart. And, as if receiving a gold star for their conviction, they get Divine.

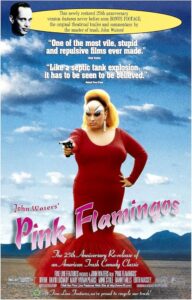

She plays “the filthiest person alive” in Pink Flamingos, as she’s been awarded by its fictional tabloids. And it’s well deserved; there would be few that could even compete. But there are two, and they are “jealous perverts” Raymond and Connie Marble (David Lochary and Mink Stole) who will do all that is in their power to rob her of the crown. In the meantime, however, she throws elaborate parties and wears deli meat between her legs.

Director John Waters made a point of naming Pink Flamingos “an exercise in poor taste.” In plain terms, that is all particular scenes can certainly amount to. And all the rumours are true. Yes, Divine picks up and ingests the defecation of a dog left on a sidewalk. Yes, the chicken was killed in that such way. Yes, indeed, it is disturbing and unholy. But, what we often leave out in the discussion of immorality is where these similar symptoms already exist—in politics, in Hollywood, on the internet, and, at times, in our own interpersonal relationships. What Pink Flamingos leaves one with is an absurd extension, a manifestation, of these habits and conditions being performed or desired already off-screen. Truly vile cruelty, yes. Cathartic, yes.

There is a common question from those not entirely won over by Waters’ audaciousness, unsure of why one would push the envelope for the sake of pushing the envelope. What they fail to grasp, or perhaps what they most fear, is if never pushed, if never even tried, there is no discovery, and there is no meeting what lies beyond social norms. Traversing past the zone of allowed behaviour is the medicine of sanity, and when we find ourselves enthralled with such transgressive indecency, this is how we are sure we exist beyond etiquette. Pushing the envelope is, in essence, the human response to an envelope. That is, one designed already in poor taste.