There is a distinct before and after when one watches just about any film by director David Lynch. Before, of course, comes in a variety of forms and experiences. But, after is often the same result: the rebirth of a once-rotten core and a palpable sensitivity to the unknown.

After Eraserhead, I felt it. And then after Mulholland Drive, and Wild at Heart. Then when I had watched Lost Highway and Inland Empire, I felt it too. It was as if I had left the theatre without the clothing I had entered in—bare to the world, chilled by the elements. Lynch’s films spoke a language I never did understand, but I believe my skin and beneath were fluent.

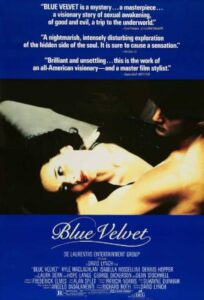

When I first watched Blue Velvet, however, no parts of me had been shifted or torn apart or reconstructed like they had during others. Maybe it had been the raisin Glosettes. And it could have been the seat, too far left to the screen. But I exited the cinema frustrated and discontent from the bitter aftertaste it had left me with. And for the several weeks afterwards, I aired my grievances to everyone who listened (and probably, almost definitely, some who didn’t).

It wasn’t until many showers later that my relationship to the film had been nurtured to maturity. It played in my mind as I sang along to Isabella Rosellini’s tragically tortured performance of the tragically sentimental song “Blue Velvet,” shampooing my hair to its rhythms. The small gestures of the film’s characters moved in my limbs without my intentions. Lines from the film crept back into my mind and tickled the matter (“Fuck you, you fucking fuck!”).

Despite the initial reception, its subsequent resentments, and what I certainly would have regretted to hear, Blue Velvet had become the film that quietly, below its surface, designed certain portions to me. And for that alone I cherish it dear to all my portions.

Blue Velvet is a neo-noir film about the loss of innocence, the uncompromising harshities of a corrupted world, and about what’s left over when one rids themselves of it—yes. But, what the film has most taught me is the challenging ways that art affects its audience. How, regardless of its intentions, it may viciously grab onto any persons who witness it. Art, I learned, is most visible in the precious and intimate relationship between the artist and audience.

When I heard the news, when all the news channels and stations I tune into reported on it, the portions of me that Lynch had manufactured felt emptied. On January 15, his family shared, Lynch had passed from emphysema brought after 68 years of cigarette smoking. His lungs had little air to sustain him with and, in an interview with People magazine, he admitted that he could “hardly walk across a room.”

When I got home that evening, after I took off my shoes and outdoor clothing, made a meal, I inserted a Blu-ray copy of Blue Velvet into my player. And while credits rolled afterwards, I felt the parts I may have lost become refastened. Kyle MacLachlan and Laura Dern mended them. Even in his absence, Lynch mended them. In this strange world, velvet, it seems, still persists through our blue veins.