There was for a long stretch during my formative life a profound seclusion under blankets, enveloped only in the everyday thoughts and experiences of my sole personhood, and with the online interaction I felt required to permit. This period involved little communication with those I was, although at a time less inclined to admit, emotionally or biologically related to. It was, too, during this period I was most fond of the individual over its antipode, the collective, and held high esteem for what she stood for alone—what she meant as a figure without social necessities. And while I struggled to call this a period of self focus, text messages and emails digitally piled around my bedroom, weighing down my moral quandary of alone or alone—and to whom my stasis benefits.

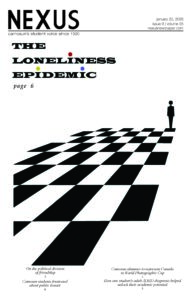

For the better half of the 21st century, and even more so in the last decade, a very pretty image has emerged of solitude: an independent, a lone wolf, a forger of many paths. The picture, which in a variety of appearances are pasted on the collective vision board, looks to reason with the ever-growing loneliness which has permeated quiet spaces between neighbours and peers. Whether it was first the hyper-capitalist messaging that formed it or the liberal-minded free-thinker who thunk it, the narrative of loneliness as a moral token of empowerment has swiftly developed, and has done so, most attractively, in a sermon of wellness.

The ethos of mainstream wellness culture in the contemporary era is perhaps best defined by its lessons of hyper-individualistic self-sufficiency which teach its patients (those who pay or those who tune in to the online sphere) that “personal growth” and “healing” are best achieved without witnesses, in privacy from our loved ones. Both the process and goal of the transaction take on this dogma: be alone to be alone well. The zeitgeist questions love and community, how it benefits, or does not benefit, the individual. And, if outsiders do not pass the litmus test of hyper-normalcy, if they misbehave, disappoint, or run high with emotion, it’s worth questioning the relationship, as it may not “serve,” waving above to below from the moral high ground.

In a puddle of guilt in my own psychologist’s office, wet around my nose from confession, I woefully admitted that my relationship with my now husband had, in ways I had not intended, I stressed, mended parts of me that I hadn’t yet had the chance to mend on my own. I had, in fact, committed mortal sin. And now, married, I was left without the chance to Eat, Pray, Love myself, as I had been told I ought to. Not that I wanted to Eat, Pray, Love, but because One Woman’s Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia is subjected to one woman, not in companion. And to find everything is most encouraged individually. But, what I believe is most offensive to the notion of healing within a relationship, and perhaps because of it, is that the accomplishment is improper and isn’t sufficient—that learning to love another isn’t instrumental to learning to love the self.

What North American wellness culture ignores, however blindly or intentionally, is that as individuals with contradictions and new facets in constant formation, we are all permissible at all times to be burned at the stake for our flaws, on the receiving end of one “protecting their peace.” In her essay “no good alone,” Rayne Fisher-Quann writes that, in this case, the contemporary therapizing suggests friction, which may be challenging to navigate, is in direct impediment to the “healthy” individual. And this, indeed, may be true. In pursuit of tolerable connection, sans texture or rough edges, one loses the discomfort of humanity and passion.

To be clear, however: conflict, incompatibilities, and asymmetry in relationships are not always agreeable to endure. There are nuances, there are limitations. But, limitations, through a contemporary wellness lens, have been lowered, a tragedy that restricts one from experiencing any friction to begin with, and finally, eliminating all faulty persons. That is to say, all persons, leaving all in profound seclusion under blankets, enveloped only in their everyday thoughts and experiences of sole personhood.

The recent zeitgeist for a moral good in solitude exists in a viscous cocktail of social and economic hindrances to form connections, and we have commodified the lifeblood and have said the lifeblood is independence.

But another, most obviously, and well-addressed among crowds paying large bills with little pay, and I include myself again, is time. Time between work. Day jobs and side hustles. They have gig jobs, freelancing, and whatever third, fourth, sometimes fifth, stream of income can assist survival. And dare they attempt to attain enough to live—share their limited time with those they love. And, data from the Surgeon General of the United States agrees.

In 2023, they issued “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,” a report which begins to understand an intersectional influence on those most affected by the epidemic. Stated in the introduction, Dr. Vivek H. Murthy writes “Loneliness is far more than just a bad feeling—it harms both individual and societal health.” And, on page 19, he finds that “lower-income adults are more likely to be lonely than those with higher incomes,” adding that 63 percent of those earning less than $50,000 per year consider themselves lonely, 10 percentage points higher than those earning over $50,000.

It is not incidental that the participation in community affairs has lowered in recent years as the cost of living has risen. $2,000 one-bedroom, one-bathroom, one-loud-neighbour apartments (not including hot water, electricity, furnishing, or smooth wall paint) are, in part, the death of the social. What more is a barrier than the financial, when the sum salary of one working a minimum wage job, $17.40 in British Columbia, allows the worker at most $36,192 per year, a significant gap between the lonely and the wealthy. And what more could one exert themselves, or pay to experience outside the home, when one is below the water, doggy paddling enough to stay afloat.

The peculiar and unintelligible concepts (I say half-jokey, half-sincere) of supply and demand, inflation, and the free market are indeed, too, the death of the once-inexpensive third place—the public gathering spaces where one may connect with another, or have the chance to connect with unknown others: cafes, bars, salons, places of worship—and in turn, the rise of the lonely individual. (The home is known as the “first place,” and the workplace the “second.”)

It is now a frighteningly distant memory, common spaces for closeness to evolve outside the home; chattering, babbling, sunlight beaming over the face for all to see. Playful. Public. Intimate. It is a time of closing libraries and dwindling clubs. It is a time of $6 lattes.

In his 2000 book Bowling Alone, referenced on a Government of Canada webpage on the rise of loneliness, Robert B. Putnam writes immediately on page 15, “No one is left from the Glenn Valley, Pennsylvania, Bridge Club who can tell us precisely when or why the group broke up, even though its forty-odd members were still playing regularly as recently as 1990, just as they had done for more than half a century.”

It is unknown among most, still today, an ongoing, more posed question: why and how we’ve arrived in a lonely continent, once known for its penchant for socializing. Why and how the distance we have manufactured for ourselves, and the entities above who have manufactured the scenario for the population, have left us stranded. Why and how the time spent alone has never felt more lonely.

A culture has changed, that is sure. Technology, and with it social media, chat rooms, video games have played a role—it is undeniable. But, although it is widely accepted as a primary source of the epidemic, I resist the claim that it is foremost. Technology has changed how one connects, but for better or for worse is individual. Indeed, there are eyes strained from the harsh blue light of a smartphone, blaring the intangible universe defined by its chaos into an easily absorbed brain, but there are, too, transnational relationships able to be preserved and nurtured from 15,000 kilometres afar. And, there are riches of human variation that can only be experienced by watching the online documented life of a small Palestinian family.

What I believe is most potent to this epidemic is a man-made secret, and it comes from the ever-exhausting, obsessive pursuit for one’s self-sufficiency and meritocracy in a continent defined by a narrow ideal of success. The idea denies assistance and support. It denies the existence of togetherness in prosperity. It is lonely at the top. And by the pillars of this virtue, it should be lonely; it is designed to be. The self-made billionaire is revered not only for his excessive profits, but his ability to do so alone, in his basement or on his tattered laptop. We glorify the trauma that is instrumental, they say, to be lonely at the top.

There lies at the very core to the loneliness epidemic the disclusion of others for the personal gain, what the result of this phenomenon suggests to observers of the success.

The case of the lonely person is noticed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has noticed it, the Canadian government has noticed it, I, and my few and far between peer interactions, have noticed it. Yet, we continue with the assumptions of permanency to this infliction, and see loneliness as a natural occurrence to a natural social structure.

I believe in bridge clubs, and the collective wellness. The kind glances and cheap cappuccinos (regardless of quality). Public parks. Bible study. Time. In a man-made North American loneliness infestation, I believe one library card may be the exit to one’s own self-imprisonment, and subsequently those around them.