It is beyond all reason and yet beyond all doubt we love what we do. And in regard to art (and in regard to film), there could be nothing more deeply and illogically adored. In other words, what is well loved, in public or otherwise, is anchored to the soul by intangible weight, inexplicable as to where one can, although it may seem strange, identify the source of attraction.

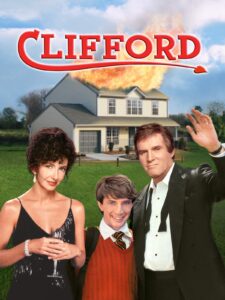

This is what comes to mind when I speak of Martin Short’s 1994 film Clifford, and its merit of my unconditional love, beyond all odds.

First disapproved by audience members, and then critics, and then by time, Clifford does not conform to certain ideas of taste.

In a review for the film, Roger Ebert wrote, “It’s bad in a new way all its own. There is something extraterrestrial about it, as if it’s based on the sense of humor of an alien race with a completely different relationship to the physical universe.”

No one may argue with that apt analysis. Short, as a 40-year-old man, plays a 10-year-old boy simply by dressing in schoolboy clothing, using forced perspective to hide his true adult stature. On route to Honolulu with his parents (Richard Kind and Jennifer Savidge), Clifford discovers their plane is passing over Los Angeles, home to Dinosaurworld—the fuel that powers Clifford as he, ridiculously, turns off the plane’s engine when introduced to the pilot, requiring an emergency landing. Wildly coincidental, Clifford’s uncle Martin (wonderfully performed by Charles Grodin) is in need of proving himself fit for parenthood to his girlfriend, Sarah Davis (Mary Steenburgen). And so it’s settled: Clifford will stay in the care of his uncle while his parents escape from him in Hawaii.

Deceptively, uncle Martin’s first impression is darling, as he finds Clifford soundly napping on an airport office sofa with a handmade banner hanging above, reading, “I LOVE MY UNCLE MARTIN.”

As their time together progresses, however, Clifford grows more and more sadistic, beginning with small practical jokes that embarrass his uncle and ending with his uncle’s sanity.

As a last minute decision, one that hardly works at all, the film is framed as an anecdote, told to a small troubled child in the year 2050 by a now wiser Clifford dressed as a priest—similar to The Princess Bride but worse.

Love does not require approval. It does not require explanation, either. Clifford, along with various other inexplicable artistic love affairs of mine, is a film that speaks not to the brain but to the very core of the human spirit.

It is in poor taste to look down upon any artwork, be it a Wayans brothers creation or a Fellini. To connect sincerely to anything is the essence of fulfilled living. It is beyond all reason that Clifford remains the essence of mine.