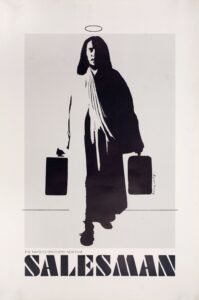

Door to door, and door to door to door, they come dressed smart with wit up their sleeves. In one hand, the holy book; in the other, clammy desperation. Although they may be Bible salesmen, the Lord is seldom on their side. Documentary film Salesman (1969)—directed by Albert Maysles, David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin—dedicates itself to the to the tireless men deep below the illusion of the American Dream.

The year is 1967; while among the Vietnam War and counterculture, four men find their limited fortunes in the pockets of New England Catholics. Peddling the luxury Bibles and Biblical encyclopedias of the Mid-American Bible Company, Paul “The Badger” Brennan, Charles “The Gipper” McDevitt, James “The Rabbit” Baker, and Raymond “The Bull” Martos travel down to Florida with entrepreneurial spirit, wishing to conquer new territory for business. Their nicknames are of no random ordain, each correlating with their respective sales techniques. The Badger is quickly understood as the focal point, not for his zeal, but what crumbs are left of it. The capitalist system has chewed up and spat out a hollow entity too old to change businesses and too young to die. On route from one unsuccessful sell to the next, The Badger sings to himself, “Wish I was a rich man, I wouldn’t be goin’ on this shit land,” a plea for a new life around the next corner block. What is often found instead is another working-class Catholic family, unwilling or, at times, unable to spare as low as a dollar a week.

The commodity the salesmen aim to market comes at a turning point: God is out, The Beatles are in, and Heaven is to be made on Earth. Little can be done to stop the projection of faith and none of the 43,000 answers available in the Catholic encyclopedia will provide a solution to this quandary. In a final scene of the film, a warped orchestratic “Yesterday” plays from a resident’s record player as The Badger makes a killing: a $26 down payment.

As pioneers of direct cinema, The Maysles brothers’ camera is a fly on the walls of mid-century homes, peering into the desolation of American normalcy and decay of what once was. Below petty grifting and phony plays are curious matters of the soul. The small subsection of American life speaks for the whole; the Dream never did exist outside the imagination.

The life of a salesman ends like many: tired, withered, and void—all the books in the world cannot interfere. It’s a tale as old as the Almighty’s good word.