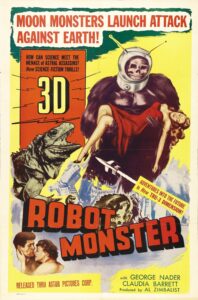

If two words effectively attract swarms of schlock-hungry audiences, they are “robot” and “monster.” Plastered in large red text across an illustrated poster, Robot Monster (1953) was a lucrative success, bringing in $1 million USD at the box office. It isn’t hard to imagine why—the picture was filmed in elegant 3D, and with a title like that, amusement is almost guaranteed.

On its very surface, the film is an abysmal B-movie classic with several gaping plot holes and novelty up the yin-yang. Its abundance of poorly executed gimmicks and the Automatic Billion Bubble Machine (accredited to N.A. Fisher Chemical Products, Inc.) is only skin deep. Below what many naively consider a staple in garbage cinema is possibly an abstract research into the mind of an eight-year-old boy overly consumed by fiction.

As the film opens, credits roll over a spread of comic-book covers. A menacing score composed by Oscar-winner Elmer Bernstein dissolves into a ditsy, childish tune as school-aged boy Johnny (Gregory Moffett) approaches over the hill, dressed in spacesuit getup. Bubbles float from out of his toy gun toward the audience’s anaglyph glasses.

As the child and his young sister Carla (Pamela Paulson) stroll through the rocky Bronson Canyon terrain, they find two clean-cut archaeologists busy at work. After a short ramble about spacemen and robots, the children are whisked away by their mother (Selena Royle) and older sister Alice (Claudia Barrett) for a routine nap.

When Johnny wakes, powerful lightning bolts strike, and up above a bright flashing light grows enormous before consuming the screen completely. A quick cut jumps immediately to a seemingly unrelated sequence of battling prehistoric reptiles.

It’s easy to mistake this scene as incoherent nonsense, but upon closer examination, it’s clear that director Phil Tucker is just getting started.

What Johnny and the audience solemnly learn is that he is among the last of six humans on Earth: himself, his two sisters, his mother, and the aforesaid archaeologists. What has happened to the rest of mankind can be attributed to Ro-Man, a portly half-gorilla, half-diver alien. He putters around his territory in a slow-moving form on account of his rotund body. Very little of him is threatening but his words are mostly clear: “Now I must kill you.”

Through the rim of Ro-Man’s diving helmet, a concealed face is covered in gauze—his only visible expression: a shake of the fist.

After a few deaths and a brief affair between a love-starved Ro-Man and a reluctant Alice, the film closes with a big twist and bookends itself with “THE END” blocked over the spread of comic-book covers, the child-like dreamscape locked in between.

Robot Monster is nothing less than a triumph in American cinema and nothing more than cheap trash. Death, destruction, pain, and glory, the timeless film is survived by an affectionate crowd of cult followers.

Pair with a glass of Plymouth gin and eat your heart out, Citizen Kane.