Throughout Victoria, there are unmarked spots where history was made. In the basement of a house on Caledonia, Green Day played a show on October 6, 1992. Near the corner of Hillside and Quadra, another house held shows with legendary punk bands NOFX and Lagwagon. World-renowned crossover hardcore legends DRI? Yup, they played in a house just off Burnside.

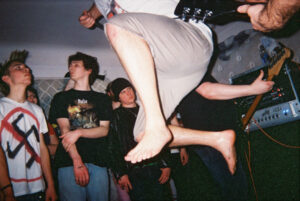

The history of Victoria basement shows is a broad topic. There were many punk houses that held them over the years, some short lived, others lasting a decade or more. Some of the older punks are no longer with us to share their stories of holding basement shows in their house. (And while we’re focusing on punk, house shows exist in many other scenes, such as folk and indie.)

One of the most infamous house shows in Victoria punk history comes courtesy of one of the most infamous bands in Victoria punk history.

Members of Dayglo Abortions lived in various houses over the years. Trevor “Spud” Hagen and Brian “Jesus Bonehead” Whitehead lived in a house on Head Street until Bonehead moved out to another house on Head Street, then to one of the most famous houses in local history for basement shows: Bonehead’s on Caledonia.

This house is still talked about for a show on October 6, 1992, when Green Day came through town and played in his basement. In the liner notes of Kerplunk, Green Day mentions Victoria, BC (as does Lagwagon in their Trashed album liner notes).

In 1985, Gary Brainless started The Rat’s Nest at 468 Cecelia Road, which was Victoria’s longest running house venue; it existed for 28 years until being torn down in 2013. Brainless held shows until the end; it started as just a fun thing to do.

“When I first moved into the house, a friend of mine mentioned that Junior, one of the guys from Nomeansno, they needed a place to jam,” says Brainless. “And so, we figured we’d have a show with The Resistance, that I just started playing drums with, and it was kind of a rehearsal for me with The Resistance. So it was so much fun, first time we did it, we just kept going.”

The Rat’s Nest hosted shows for DRI, SNFU, DOA, MDC, Clown Alley, Angry Planet, and hundreds of other bands; it was known across Canada and the US. The sheer volume of shows that took place at The Rat’s Nest and the number of years that it ran for is a sobering thought.

Ty Stranglehold of local punks Knife Manual has fond memories of being at The Rat’s Nest.

“It’s funny because the one thing I don’t remember is the bands on this given day, but I just remember being at The Rat’s Nest and just crammed in,” says Stranglehold. “You had to sort of fight your way down the stairs to get to where you can see the band and just being sort of wedged in and, just being in this tiny basement with, I don’t know, it seemed like hundreds of people, but it wasn’t. And everyone’s just there doing the same thing, there for the same reason, and just smiles and having fun and just the band just going off. And then, you know, you can’t take it for too long and you’re like, okay, I gotta go back upstairs. And it’s still packed upstairs and you’re hanging out in the kitchen, and it was amazing because there was literally taped posters on every wall, every ceiling, every surface from the decade, or a decade and a half before that, of bands playing The Rat’s Nest.”

He says that shows at The Rat’s Nest served a purpose beyond just hearing some great underground music.

“So, you would just be standing there and taking a breath, looking around and there’s so much to see and there’s so much history there,” says Stranglehold. “It just felt so important at the time as well because there’s history here. But there’s also a present here, and it’s serving the needs of our punk rock community now, as it was in 1985, and then it would continue for another five to 10 years after that. And just that feeling of being a part of something and… the house was a visual, sort of a structural representation of that community need, or community service.”

The House of Trash was another long-running punk house—it lasted about 10 years and was started by Hoon, bassist of local punks The Gnar Gnars, on Tillicum Road. Aside from having shows, The House of Trash was a rehearsal space for bands that needed somewhere to practice, a place for touring bands to stay, and an after-party venue that became a well-known hospitable punk house.

“There’s a band from LA called Static, they were on Hellcat Records. There’s an all-female band, Civet. They were also from Los Angeles on Hellcat, and they came through and played,” says Hoon. “I don’t remember which bar in town, but I met them, and I was talking to the girls, and they mentioned that they didn’t have anywhere to go, and they were gonna sleep in their van. So, we invited them back to the house to sleep in the basement on the couches. And then we all ended up having a party and we all jammed together. And then when they went back to LA they were speaking to Static, who were coming through. And then when those guys came in when they played Lucky Bar, they were out walking around asking people for me, like, ‘Hey, does anybody know a guy named Hoon?’ Everybody knew me, but I wasn’t there yet. I showed up closer to the time the bands go on stage, as opposed to earlier, and everybody told me they were looking for me.”

Static ended up connecting with Hoon that night and were grateful to have a place to stay. They also crashed at The House of Trash two more times while touring through Victoria. Many other bands either stayed at or played The House of Trash, such as Royal Red Brigade from Regina, East Vamps and JP5 from Vancouver, Spastic Panthers from Calgary, and Yer Mum from Winnipeg.

CFUV music director Troy Lemberg was one part of Troyler House, which was located at 3401 Shelbourne Street. Soon to be demolished, it ran from 2009 to 2013 and held a total of 43 shows.

“It’s a weird little house because it’s a two-bedroom house with a backyard,” says Lemberg. “But with a band, when we have a full metal band in there with multiple full stacks, because we put mattresses at the windows, if you went out on the sidewalk, it just sounds like someone had their stereo on, which is so ideal for that space—it sounds like nothing was happening. There’s just the people smoking out back, which is where we have to be quiet.”

Before the internet, discovering where the basement shows were was done mostly by word of mouth. Posters and handbills were used to help get the word out but usually it was a friend who knew a friend. Even today, word of mouth is how someone finds out about a Facebook page for a house that holds shows. A key factor in successfully holding shows in a house, or even having bands rehearse there, is the neighbours. If there isn’t a good relationship with the neighbours, the basement shows won’t survive long. The Dayglos ran into trouble with their neighbours at their first house, where they rehearsed.

“We never had [shows]. The place wasn’t very well insulated,” says Spud. “We had a little neighbour across the street, and he would call the cops on us every time. They figured out that we practiced on like Wednesdays and Sundays or something like that. So, he started calling the cops before we even got together so the cops would show up, we’d be sitting there, like we’re not playing. So, they were making false reports to the police; they’re an old European couple.”

The Dayglos—no strangers to legal controversies—finally went to court with the neighbours.

“I think the judge is pretty funny. It turned out to be quite a humorous little event at the court. And in the end, the judge was giving everybody a certain fine with so much time, or such fine or three days default or something like that,” says Spud. “We went through ours and it was a joke. Everybody in the courtroom was laughing quite a bit and… like, $50, no default. ‘What? Oh shit, that means I don’t have to pay?’ So, we decided we weren’t going to have band practice there anymore.”

Being partly underground helped to control the volume coming from The House of Trash. However, the agreement the tenants had with their neighbours on when shows could take place also contributed to its longevity. The house was across from the Gorge Pointe Pub; both the house and pub are no longer there.

“They tore it down and built condos,” says Hoon. “But at the time the house was a side-by-side duplex, and when we first moved in, [the neighbours] had two kids and they were super cool. The day we moved in, buddy came over and said, ‘I don’t care what you do here. Sunday through Thursday. Stop the noise at 10 o’clock. Friday and Saturday it’s fair game, man. We’re going to be drinking in the backyard, we’re gonna be doing our thing, too. Don’t complain about me, we won’t complain about you.’ And we made a deal, and there was always an understanding between us… We’re very fortunate. They were pretty cool about that. But that’s kind of rare.”

Maintaining that good relationship doesn’t stop at respecting the rules of when shows can take place. There’s a level of common-sense respect for the neighbourhood, especially when it comes to keeping it clean.

“I only had one neighbour and that was my next-door neighbour,” says Brainless. “Look, the only two houses on the block are side by side and I got along with them if I cleaned up the messes. You show respect, clean up, and usually there is a mess, beer cans everywhere, whatever, clean up the shit. Usually, people are pretty good with it.”

Quadra House, run by Rylan Michael, currently has shows once a month, featuring local and touring bands. It’s been running for about two years. They have it down to a science. They have a strict 10 pm end for bands that are playing and large bins for empties near the door to encourage people to clean up after themselves. According to Michael, people generally leave right away and are completely cleared out by 11 pm.

“We’re really lucky, we really only have the one neighbour on our right, gas station is on our left and we have a pretty big yard in the back,” says Michael. “But the neighbours on the right, we’re very lucky, they’re super, super awesome. That’s the reason we only do one a month, is for them. As the reason we shut down by 10 is also for the neighbours. All they really asked me was like, don’t do it every week and you stop the noise by 10. We’ll leave you alone and they’ve been true to their word in two years. And we’ve never had the police here.”

The reasons for having shows in a house are a mix of fun, money, and keeping the local music scene alive. Any money raised from modest door prices goes to touring bands to help with the cost of the ferry, and sometimes to help punks make ends meet.

“Money. I mean, really, why? I mean, it’s fun to do, yes. Honestly,” says Spud. “Yeah, we charge a couple of bucks to get in, that pays for all of your booze and whatever else you’re doing that night and if you’re lucky, maybe pay rent. So, if you’re charging a couple bucks to get through and 50 people come in, there’s 100 bucks… I wouldn’t say it’s greed but it’s money. You can get some coin because what punk doesn’t need a few extra bucks?”

Both The Rat’s Nest and Quadra House both started from one night being so much fun they simply kept putting on shows. The money from The Rat’s Nest went to ensure bands had money for food and the ferry. Brainless didn’t want bands paying to play, which was often the standard at other non-house venues. Quadra House was inspired by a birthday party.

“The first show was just a birthday party for my girlfriend,” says Michael. “And so many fucking people came and had such a good time and [I] was just starting to play [in] bands again, looking for shows. There was not a lot of venues at all. The first show party thing went so well I said, ‘Fuck it. I’ll do this every month if I can.’”

The House of Trash started as a jam space where bands could rent rehearsal space. Hoon says they also hosted after-parties and would have Saturday evening or Sunday afternoon shows for touring bands to earn a bit of extra money to cover costs. It eventually grew into being a well-known place for bands to stay, get cleaned up, and head back out on the road.

“I knew what it was like being on tour and having nowhere to go and nothing to do, so we always offered things when the bands came through. We were like, ‘Hey, we got clean towels for you guys, want to shower? You guys want to do some laundry? You know, get yourself kind of clean so that when you leave the island and head back to where you’re going…’ Because usually, we were a turnaround spot, Victoria,” says Hoon. “We tried to make big meals. If I knew the guys in the band, I knew their dietary restrictions, or else we make two chilis—a meat chili and a veggie chili—and just try and feed everybody and then try to send them out with the leftovers if they want it, because I know what it’s like being on the road and starving and stinking because you haven’t had a shower in three days.”

With the hundreds of bands that have come through the various Victoria punk house venues, locals have, of course, many memories of shows. However, it wasn’t just watching the shows that was memorable.

“Just the bands and some of the people… Through the years, they’ve just been incredible,” says Brainless. “So, a lot of those friends are still my friends no matter where they are in the world. I think people get to hang out and meet without fear, persecution, or anything like that.”

One thing that’s often misunderstood about punks is their attitude. While there are some who just want to stir up trouble, there is also a strong bond of community; they look out for each other and those around them.

“We were the people that were up at three in the morning,” says Hoon. “And, you know, drinking beer or whatever, just eyes on the street. One time I saw somebody across the street going to this old lady’s [house] and I didn’t really know but I knew there was an old lady that lived there. I saw this guy snooping around on the property. I grabbed a couple guys, and we went across the street and fucking confronted the person. They had no right being there by any means, and we were yelling at them to get out and they got out and the old lady woke up and came out and she saw that we were getting rid of this person that was up to no good. They hadn’t stolen anything yet or broken anything yet, but they were there definitely trespassing and not supposed to be there. And that kind of spread like wildfire through the neighbourhood, and all the neighbours knew that we were kind of looking out for them.”

An honest history of Victoria basement shows wouldn’t be complete without stories of cops showing up, and there were more than a couple times that happened. Brainless recalls a night in the late ’80s or early ’90s when a paddy wagon was parked on his lawn and started hauling people off the deck. There were about 200 people outside that didn’t get into the house. Spud tells a story of punks versus rockers where the punks weren’t the instigators of the cops showing up and Dayglos ended up playing to a riot outside the house.

“I think it was ’78, and the house wasn’t really a punk rock house, which was Wally’s down in James Bay,” says Spud. “I can’t remember what the name of the house was. He asked us, he says, ‘You want to play?’ ‘We’ll do a show there. Sure.’ So, you know, we figured okay, well, it’s just gonna be like a party. So, we’re gonna charge like two bucks a person to get through the door just to, you know, pay for our expenses and shit like that. Wally was all good with that.”

What Spud and his band didn’t know is that the people who lived next door had abandoned the house and taken off, and the owner’s 14-year-old daughter decided to throw a party there. So 200 people showed up at that house, and there was maybe 50 people at the house show next door.

“So, they wanted to come in because it was live music and we told them no, you can come in and pay two bucks if you want,” says Spud. “But it’s not that party over there, this is separate, just happened to be in the same night. The cops showed up. So, we went to our house and the cops actually came over to Wally’s house and said, because I guess they knew him or something like that, ‘Look, keep everybody inside. You guys aren’t the ones that are causing problems. We got to clear this out.’”

Then things got real bad, although, for once, it wasn’t the punks at the receiving end of things.

“Next thing you know, boom, it’s like stormtroopers coming down with fucking batons out, and shields and just scared the fuck out of everybody,” says Spud. “So, they ran away, and then after [the cops] cleared the other party out, they came over and said, ‘Okay, well, you’re going to have to close yours down too, but don’t worry, we’re leaving. But you gotta close it down.’ [Wally’s] like, ‘Yep, no problem at all.’ All the rockers ended up getting a shit kicking from the cops, but we were all fine. Which is nice.”

It all adds up to unforgettable memories, whether that’s Billy Joe Armstrong playing his heart out inches away from the audience in a basement with walls dripping with sweat or getting to share the “stage” with bands that may not be selling out the arena, but have created moments even more special in houses in Victoria.

“One of the most memorable ones for me was when our friends from Ontario, EndProgram came through, I think it was [drummer] Chris Boneless’ birthday,” says Hoon. “And we had a show, we played, I think was probably Logan’s, and then we did a show in my basement. The Dayglos were there and Chris Boneless played bass for the Dayglos at my house at a party and that was super memorable, and it was like a dream come true for him.”