Living in Victoria is living in an urban fantasy. My commute to work or school is greeted with cautiously curious deer, or ominous crows, or the neighbourhood cats. Tamed flowers in people’s gardens burst into bloom in spring, and vibrant, fiery leaves drop from their branches in autumn. This sensory life cycle constantly changes around me, and I change with it. I hide myself in my cozy shelter when the rain falls on my roof, I feel alert and energetic under the shining eye of the sun, and I reflect in the serenity and mystery of the moon. I feel a spiritual certainty when I am with nature. Would my ancestors have felt the same?

Yet we are living in a city, just across from the hyper urbanism that is Vancouver. I can channel the secrets of nature and think nothing of it: there’s lightning in my walls that I can control; I can turn on fire; I can change the temperature of water that runs from the tap. I even have a metal rod fastened to the back of my teeth to keep them straight. We’re living beyond nature, and it’s gotten to the point where if we continue to consume and waste what nature has provided for us in such a rapid manner, there won’t be a place on Earth for life.

Earth, now, is a complete jumble of human influence. We tell stories of a totally technical world, where trees are considered alien creatures, as a warning of what will happen if we don’t turn back. Climate change is now declared a global emergency; the UN has released a new climate report directing us on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. If only there were a stage direction that read, “Enter a solution.” If only we had a holy intervention that changed the hearts of every politician, CEO, and billionaire to say, “Look, how about we stop pumping oil in the ocean, and reverse the 100-plus years of damage we caused.”

A 2017 report announced that only 100 major companies are responsible for 71 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, I’m in a “100-percent environmentally friendly” store, debating if I should get a metal straw. I don’t even use straws. Industrial expansion is overwhelming the state of the planet. It just might be impossible for all of us to tear down our cities and live off the land, because there’s not enough land for us all.

I can’t help but feel hopeless as I buy another facemask with the words “organic” and “fair trade” slapped on the recycled packaging.

That is, I felt hopeless until I spoke with the experts. If anyone would know anything about climate change, it would be the people studying sustainability, biology, and environmental technology. While the damage against the Earth is at an all-time high, there is, as it turns out, endless hope for the future.

I started looking for answers, and I started looking for answers right here at Camosun College.

I wanted to know what Camosun was doing with its environmental initiatives; the person to talk to was Camosun manager of sustainability Maria Bremner. Bremner is completely confident in her plans and speaks with a realistic hope in her voice.

“I think that we do need to make a big cultural change,” says Bremner. “Whether it’s how we purchase or how we make transportation decisions, those incentives’ measures have to be at the right level. There needs to be, on one hand, an appeal to economic and financial incentives, but on the other side of the coin, helping people see how that it’s also about improving quality of life.”

Most of these incentives on campus revolve around transportation.

“We’ve implemented some financial discounts on secure bike parking, and the student society has been a great leader in helping support the UPass as an incentive,” says Bremner. “I think we’ve really seen that as a great example of how a free bus pass that is built into the annual student fees can really change people’s behaviour. It’s free, they don’t have to pay for parking, it gets them to campus in a sustainable way, it keeps the roads and the air from being congested with harmful polluting. Hopefully we will instil lifelong behaviours that they will consider sustainable transportation in the future.”

As part of Camosun’s Sustainability Plan, the college is ready to launch an electric bus as a new transportation alternative for students and staff on the Westshore this September. But Bremner’s plans don’t end there. She is always considering the next steps in encouraging an eco-conscious philosophy in students.

“I think there’s other things, where you could have not-paper-based textbooks, where you’re saving people money that way,” she says. “[Another] example may be food, and different incentives for healthier food choices. It’s not just about finding local options, but options that are more affordable and healthier.”

Environmental Technology and Electronics and Computer Engineering instructor Ian Browning says that students have been showing an interest in making environmentally sustainable projects.

“On the Electronics side, over the last few years, there have been various projects students have been doing on renewable energy systems,” he says. “For example, one group did a sun tracking system, so solar panel trackers to make it more efficient. We’ve had things like composting systems people have done as well to prove the efficiency of composting. On the Environmental Technology side, there have been various ecological restoration projects, so working with different organizations on restoring particular ecosystems, for example, the stream or Garry Oak meadow.”

Browning says that the college has an eye to the environment with its architecture, as well, pointing to the new Alex & Jo Campbell Centre for Health and Wellness at Interurban as an example.

“I think they’re doing a pretty good job on that already,” he says. “My knowledge of it is that it’s sort of a passive design, so it’s designed to be partially heated by sunlight, and lighted. It’s also got things like rainwater capture and stormwater management features.”

He adds that environmental architecture will take time to be energy efficient, and that there’s also a cost involved.

“Obviously, the college is operating with limited money, so we’d need the government to step in and say, ‘Here’s $7,000,000 to do all this work.’ That is sort of happening, but is it happening fast enough? Probably not. But again, it’s all about money.”

Camosun College Student Society (CCSS) sustainability director Tamara Bonsdorf is currently building projects in preparation for the CCSS’ Sustainability Day, taking place on October 17 at the Interurban campus. She’s working on building three “pillars,” one each for food, transport, and waste.

“In the food pillar, we’re going to work with the Culinary department [and] the Culinary students to get vegan tasters to be made to give out to the students for free and to start that conversation about how cutting out meat can help the environment, and also hopefully talk about fair trade and buying local.”

Bonsdorf says that seeing what would affect students in their daily lives is important. She says that transportation is a big one for students at the Interurban campus because they are having a hard time finding parking there. The college will be on hand at Sustainability Day talking about its Park and Ride/Walk program.

“[The program] is set up with a couple other businesses that will have parking for the students and then they can make their way from those places to campus,” says Bonsdorf. “So letting people know about that, and the Camosun Express between the two campuses, helping organize carpools, and having a bike tune-up station to help them be more comfortable with biking.”

Bonsdorf is talking with the college’s Facilities department to get information for the waste pillar.

“They do waste audits every few years, so we’re going to do a small one for [Sustainability Day] where we take a week’s worth of waste from one of the buildings and sort it out in the open and show how much that could have been diverted if it had been properly sorted,” she says. “Also just raising awareness on single-use products. A lot of coffee cups end up getting used where they could have been easily replaced.”

Climate change isn’t the type of issue that can be solved locally, but more urgent action could lead to taking part in a global response. While students who specialize in earth sciences and environmental studies have a deeper understanding of how human interference damages the Earth, there are questions as to how Camosun can promote an eco-conscious lifestyle inside and outside the classroom. As an educational institution, Camosun holds the power to demonstrate and encourage awareness of the world we live in.

“I have some other ideas for events I want to do later on in the year,” says Bonsdorf. “[Sustainability Day] is the main thing that’s coming up, but in the fall I was also talking to [Camosun] about doing an ‘I don’t know’ bin in the waste station with the paper and the landfill—having a bin that says ‘I don’t know,’ and get an idea of what students are confused about, because they know it’s a problem, but [Facilities] are trying to find the best way for the students to know where things go. I think UBC have their own facility on campus, and they do all their recycling programs. But that’s just pretty expensive, and it needs full-time workers, so that’s out of the scope for Camosun. Another idea I have for a future event would be to have something with pollinator plants or indigenous plants to give out to students to start that discussion.”

Environmental Technology and Biology instructor Annette Dehalt also pitched her ideas for encouraging larger changes to Camosun.

“I’m part of the ‘animal ethics on campus’ community of practice,” she says. “We’ve lobbied the cafeteria in order to have, for instance, ‘meatless Monday.’ So far there is resistance—we usually get the answer, ‘Well, there is a lot of vegan options.’ I think as an educational institution, maybe there has to be direction from some higher-up to make it an educational experience. There’s free bus passes, so maybe we can subsidize healthier diet choices. [For] some people who’ve never tried non-animal proteins, it could be subsidized just like bus passes being subsidized.”

Browning says that methods of educating students within the classroom vary.

“How do we bring this environmental knowledge to areas other than the ones like Environmental Technology? I think various faculty make efforts to bring that into the classrooms through projects or writing assignments, but I’m not sure if there’s a clear policy to do that,” he says. “I think it’s just sort of happening naturally, because a lot of faculty are concerned about that, so they find ways to incorporate it into their subjects where they can.”

On campus, the changes are difficult for students to notice. Second-year Arts and Science student and CCSS women’s director Shayan de Luna-Bueno says that lots goes on behind the scenes.

“The [CCSS] sustainability director does a lot of work with localizing sustainable development and trying to get more community engagement and climate initiative. So, [that’s] kind of more on the lower scale.”

Third-year General Science student Carmon Salomonsson says that because he’s busy he probably isn’t aware of what the college is doing as far as environmental initiatives go. “But they’re not really reaching the busy people,” he says, “so maybe on the website, like on D2L, on the front page, they could have [something that says], ‘This is what we’re doing to tackle climate change on the college campuses.’”

First-year Computer Engineering student Wakan Tomita says it’s important to pay attention to environmental issues because of all the changes going on around us.

“We should definitely stop climate change because all the animals are really dying,” says Tomita, “and the ice keeps melting, and the water keeps rising.”

There was a phrase nearly everyone I spoke with for this story said: “Not just Camosun.” It evoked a feeling of community beyond the campus, and even beyond the city. The main concept I found among the people I interviewed was that changing all of our own lives could lead to a positive eco-revolution. Being eco-friendly is beyond trendy; the online excitement over a pneumatic fish tube in Washington proves that.

Dehalt feels positive that there is growing change and awareness for buying more environmentally friendly products.

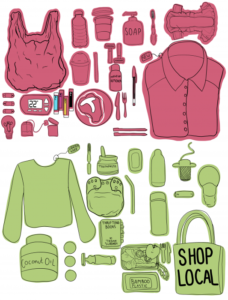

“I’m all for it; I use reusable bags myself,” she says. “I think there should be a shift from recycling to the other two Rs: reduce, reuse. You have a plastic bag—wash it a few times. Or don’t use it in the first place. A lot of things still come automatically in plastic bags. I wish there were more options in grocery stores to avoid it, but I think with consumer pressure, it’ll happen. The world is drowning in plastic; there’s more than can be recycled. Really, reducing should be the first action. Then reusing, then recycling. Simply separating your garbage, in other words. People say, ‘Oh, I recycle.’ It’s really not enough.”

Dehalt says that the reaction to climate change should be non-discriminate in geography. “There’s great urgency,” she says. “I think you’ve got to make the change where you are. I understand that Camosun or any other business doesn’t want to make any top-down decisions, or say, ‘Okay, you can’t use your car to get to campus, or you can’t have meat or dairy in the cafeteria.’ It’s difficult for any one food provider, or any one educational institution or any one business, to make choices because those customers might not be ready for that change and go elsewhere. People, as long as there’s an option to opt out and let others make the change… As long as they have a chance to opt out, they will. Those that are trying to force change for the better, they may lose business.”

Dehalt says that what you do is more important than who you are.

“I think students, faculty, and staff are all the same, with the choices we make every day. Like I said, transport and diet are the biggest ones. It comes down to these small choices. I tell my students they make choices about the environment, about animal welfare, three times a day. Every time you eat, every time you go to the grocery store. All your other products included, too. Look at the impact, look at what the packaging is, [and] look at the contents. It should become part of everybody’s lifestyle. It kind of comes as a second nature. I’m not sure we’re there yet.”

Browning says environmental technology is going to be “coincidentally important” in the future of the world; in fact, he thinks it already is.

“It seems like we’ll transition to electrification in transport systems,” he says. “Renewable energy, also, is just going to grow, grow, grow. All kinds of technology… increased efficiency of resource use. Basically, I just think all of those are going to increase just by economic necessity as well as environmental necessity.”

Browning says that unifying as a society will lead to a more beneficial change.

“I know things do take time to change, but I think a lot of the things could be done much faster than are being done,” he says. “Camosun’s making some great efforts to do that, but just as a society in general, we haven’t gotten up to speed yet.”

Browning says that being environmentally conscious in daily life is a very important step to take to raise people’s awareness.

“Even if you can say, ‘Well, just one plastic bag won’t make a difference,’ but it’s raising people’s awareness that there are issues in getting us to think differently, and to slowly modify our lifestyles to be left with something that’s less damaging,” he says.

Some students agree with Dehalt that, in 2019, being environmentally conscious goes beyond recycling.

“[I] lessen my consumption and, instead of using plastic, use reusable things,” says de Luna-Bueno. “But really, [I] just cut back on how much I buy and consume.”

I realize there isn’t anything necessarily wrong or counter-productive in being aware of what I’m doing for the environment. Most of what I do isn’t even necessarily a conscious thought in regard to being “eco-friendly.” Maybe the fact that we as individuals can’t change the world is a good thing, and joining together to make amends in our lives and willingly educate ourselves on the matters of our ecosystems will strengthen our bonds with the Earth and each other.

Buying local products—anything from home-grown foods to bags and clothes made by independent artists—or cutting meat out of your diet or paying a little more for a silicone alternative is worth it. As we progress in technology and industry, I realize more that we as a species cannot exist relying on ourselves.

I think of how often in fiction we talk about how the end of days is coming, and how we need to prepare for a post-apocalyptic world. Why should we wait for the world to end before we start caring? So I’ll go ahead and wear that cruelty-free makeup and wash it off with coconut oil. I’ll buy my books second-hand, and wear sweaters when I’m cold. Instead of buying into the waste, I’ll opt for a tea infuser and bring my own mugs to cafes.

We can’t drop everything and live as naturally as possible, but we can transition into a sustainable life. I think now that this is what it means to be a human being; I think we need to start giving back.