Artist, poet, and Simon Fraser University instructor Chantal Gibson presents altered text and history books in a sculptural re-telling of Canada’s whites-only historical narrative in her exhibit How She Read: Confronting the Romance of Empire. Gibson went to high school in Mackenzie, BC, and when she was younger, her mother—an African-Canadian woman who grew up in Nova Scotia—passed along a family legend involving black loyalists. But when Gibson set out to learn more about her ancestors she was confronted with total silence regarding the lives and contributions of black Canadians throughout our shared history.

“I started doing this work over 20 years ago in grad school,” says Gibson. “I was looking at mapping the black loyalists and when they would appear in Canadian history texts, and so I read I think 35 different books and waited for loyalists to become black loyalists.”

It was the collective experience of searching for family roots, reading Lawrence Hill’s 2007 novel The Book of Negroes,and downloading passenger lists of immigrants who sailed into Halifax that spurred Gibson’s interest in the black population of Canada.

“I don’t claim to know what folks would have said but I know, historically, that people were here,” says Gibson, “and I know that they were talking.”

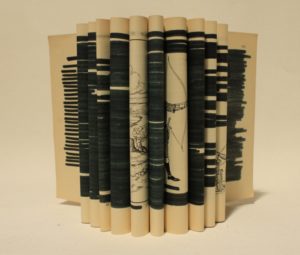

How She Read: Confronting the Romance of Empire includes large-scale prints of redacted text lifted from children’s vocabulary spellers, as well as a series of old history books altered beyond recognition through acts of black-thread embroidery. Gibson describes this work as an opportunity to imagine into being the voices of those who have been ignored or misrepresented.

“For me, the braided texts with the black thread, the premise that I try to work with is if you took away the white space—so if you look at the metaphor of the page—what would the text do? What would the black text do? And I just really meditated on this idea of those romanized letters becoming 3D and creating a form,” she says.

Gibson learned early that books are precious objects but came to believe that the content of many books, especially the records of hegemony, cannot continue unchallenged.

“A larger ideological functioning of books, of history books, is that you can’t change them, you can’t alter them because they’re sacred,” she says. “But they’re inaccurate, so, for me, once I cut my first book, I was good.”

Gibson will also present a satellite exhibition of her 17-foot-long book TOME at UVic’s McPherson Library during January and February. Made of piles of repurposed cotton and coffee, the economic drivers of the slave trade, TOME offers an alternative approach to reading about black history.

“I’m a firm believer in there’s creativity in struggle and so that’s really what I think about,” she says. “I’m not interested in narratives that [are] victimizing narratives. I’m really interested in how people who were oppressed and marginalized were creative throughout their suffering.”

In addition, Gibson will launch her first collection of critical poetry, also titled How She Read, in late February with readings at Open Space and at UVic. The poems are presented in three sections and touch on the education her mother received from the textbooks she was assigned to read at school. Gibson says that, in these books, white people were always shown as civilized and productive, while brown people were represented as tiny and magical and not quite real.

“We were all children once and nobody escapes this colonialism; nobody comes out scot-free,” she says. “Even if you are the most privileged person [you] spend your life looking over your shoulder because you know inequality exists, and sometimes people don’t understand.”

How She Read: Confronting the Romance of Empire

Until Tuesday, February 26

Open Space

openspace.ca