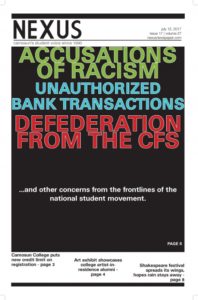

As Camosun students go about their day—running to class, studying late, drinking ultra-caffeinated cafeteria coffee—many remain unaware that they are walking on top of a tension-filled world of student politics. And it’s one that they pay into through membership fees to the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) and the British Columbia Federation of Students (BCFS). Camosun students pay into both of these organizations through their Camosun College Student Society (CCSS) membership fees every semester, but what’s happening behind the scenes—and with students’ money—goes unnoticed by most.

But these political realities actually do affect each and every student enrolled at Camosun, sometimes just in quiet and covert—but always powerful—ways. Twice a year, any Camosun student, as a paying member of the CFS and BCFS, could walk into an annual or semi-annual meeting held by the CFS and voice any concerns or appreciations they have for the national student movement. However, generally speaking, they don’t. Instead, the CCSS sends staff and elected student officials to the meetings, as they did to the recent one in Ottawa, held from June 5 to 7. And if anyone’s still thinking student politics don’t matter, consider that at this meeting, members received the results of an audit of unauthorized CFS bank transactions (this information was not made public, but Nexus obtained a copy of the audit) and a CCSS staffperson was allegedly perceived as being racist for asking if a smudging ceremony could be moved from the room because it was giving him an asthma attack.

CCSS external executive Rachael Grant says that the atmosphere at CFS meetings when she first started going to them was conducive to students being heard. Now, she says, as a result of political differences between the national CFS office and BC provincial member locals, alleged racism directed at members of the CCSS, filibustering, and a general lack of transparency, that is “no longer a reality.”

“The meat and potatoes of the student movement aren’t there anymore,” she says.

CFS treasurer Peyton Veitch disagrees with Grant, saying that the CFS continues to fight for better education for students across the country and has been responsive to its members’ requests for information (this has long been a point of contention for BC member locals, who claim the national organization won’t reply to their requests for financial and other information).

When Camosun students paid—through their CCSS fees—for four CCSS delegates (one of whom was Grant) to fly to Ottawa last month to attend the semi-annual CFS meeting, an array of events that Camosun students should know about took place, many of which we’ll discuss in this story. The semi-annual general meeting was also where Coty Zachariah stepped into the position of CFS chairperson (replacing Bilan Arte).

Zachariah says he has his sights set on listening to members’ concerns.

“It was a little daunting at first,” he says about stepping into the chairperson position. “I wasn’t sure how effective I could be. But I also saw an opportunity to right the course of the ship and bring some cohesion back to the movement. I remember when we used to get things done. I think we have to have some tough conversations.”

Also of note is that, before the meeting, a petition from Camosun students to begin the process of the CCSS defederating from the CFS was submitted to the CFS. (However, defederation will prove impossible because, as we previously reported, the CCSS has been remitting Camosun students’ CFS fees to the BCFS, which has not been giving them to the CFS; because a member local cannot defederate from the CFS with fees outstanding, defederation will not be able to happen until the BCFS remits those Camosun student fees to the CFS.)

Here in 2017, we’re lucky: we get to witness the fascinating progression of the national student movement in Canada. But a lot of it is going on at these meetings and behind closed doors, with few students around. So let’s walk through some of the issues that are currently being dealt with. Opinions about what are the facts will, as usual, vary along the way.

Hard to breathe

“Look, I think it’s good that this tradition of sage burning has started; I have no issue with it, but it is impeding my ability to represent the membership that I’ve come to represent. I have to leave the meeting for two hours at a time.”

This is what CCSS student services coordinator Michael Glover said to the disability caucus at the CFS meeting after delegates from Ontario, whose names he was unable to provide, said that Glover having a bad asthma attack and asking if the sage burning could take place elsewhere was “whiteness being imposed.”

“I reiterated that this is a health issue. This is not me trying to be racist,” says Glover. “Ideally, I think students having a national voice is good; under these conditions I don’t think that that’s possible, but conditions could change. We’re not looking to destroy anything here.”

Glover, who was born with severe asthma, started having the attack after the smudging ceremony started. Glover says such a strong accusation was jumped to so quickly because a long history of disagreement exists between BC and Ontario members of the CFS.

“There’s this polarization between Ontario and BC,” says Glover. “Any time anybody from BC does something, the Ontarioites get all up in arms, and they’re all worried that we’re trying to pull something.”

According to Glover, the word “whiteness” was used in place of “racism” by delegates from Ontario. Glover says the Ontario delegates played games to try to drown out British Columbia’s student voice and to attack him and the people who supported him.

“[Whiteness is] a very intellectual, sort of eye-level sociology term,” says Glover. “It’s to say that the society has a hierarchy based on colour, and the whiter you are perceived, the higher your status is; I’m primary white, so my whiteness is pretty high.”

But Glover says it’s concerning to him that we live in a society where so many things—in his case, voicing concerns around the effects of smudging on his asthma—are deemed to be linked with somebody’s skin colour and therefore can be interpreted as racist.

“In the anti-oppression workshop, my coordinator said, ‘There are just things where the question of whiteness just cannot be questioned. We’re not here to debate that. That’s a fact.’ And I’m like, ‘Okay, hold on here. We can always have discussions about what something means and how it is.’ So you’ve got a lot of young people with some pretty big intellectual ideas and they’re throwing them around. This is what they tried to do with me, and I pushed back. I said, ‘Look, I can die. This is not a game. I can, literally, die. Students paid for me to come here, so that seems pretty disrespectful to those students, and to me.’”

Glover adds that, despite the usual hostilities in the air, a slight speck of optimism was present at the meeting.

“By the end of the meeting I was pleased that there was at least people starting to cross the floor to say, ‘Well, hang on a minute; what’s going on here?’ People seemed less intractable on finding, perhaps, solutions,” says Glover. “I wouldn’t say that there’s a lot of hope, but I would say a glimmer of hope that people might try to get past this political nonsense.”

Glover says that Zachariah came to talk to him while at the meeting regarding the concerns he raised. The two had a discussion around how Zachariah had perceived Glover’s request to move the smudging “possibly to be an attack,” says Glover.

“I absolutely understand that,” says Glover. “It’s very charged here; lots of things have been used by both sides in ways that maybe aren’t appropriate. I said, ‘I’m not doing that.’ And he said, ‘I recognize that, and I’m sorry.’”

Zachariah confirms that he initially perceived Glover’s concerns in a negative manner.

“That was my mistake, and that’s why I apologized to Michael,” says Zachariah. “I’m really glad that we had that conversation.”

Don’t wait up

Veitch says that the meeting was “positive and productive,” and says that having a space where students can unite to discuss issues is essential to the national student movement.

“A lot of students that were there were first-time delegates,” says Veitch, “and I sensed that they came away from the meeting with a sense of optimism.”

Grant, however, came away from the meeting with a far less optimistic view.

“The meeting was not run efficiently,” she says. “The folks chairing the individual portions of the meeting were not well equipped to do so using Robert’s Rules. A lot of filibustering did happen, and it’s quite intentional, to prevent conversations happening that were overdue.” (Grant says that there were motions from two meetings back that had still not been dealt with, meaning that the upcoming AGM happening in the fall will feature motions left over from 2016.)

But Veitch says it is sometimes a struggle to find a balance between running a meeting efficiently and making sure that each motion is dealt with diligently. (Veitch also says that leftover motions will be dealt with at the November meeting.)

“There were dozens and dozens of questions that were asked in budget committee alone, and we made sure that people were heard and had opportunities to be heard. I do think that we’re really trying our best to make sure that all voices are heard,” says Veitch.

Extending plenary sessions is key for Zachariah, who says he’s not in favour of a session ending before all its motions have been dealt with.

“Looking at the structure of our meetings will be a critical conversation,” says Zachariah.

Grant says there were a few motions requested by BC locals that were never put on the agenda because they were deemed out of order by the national executive. Why they were considered out of order was never conveyed, says Grant. (These motions included one from the Selkirk College Students’ Union to remove Arte as chairperson.)

“That’s not something that the national executive, in any capacity, has the authority to call,” says Grant (Veitch says that they do, in fact, have the authority to do that). “That’s something that the opening plenary or the body of students at that meeting can vote yes or no [to]. The decision was made by folks on the national executive in some capacity to block those motions from ever coming to the agenda.”

There was an attempt for some of them to be served as emergency motions, but Grant says this didn’t happen.

“It never even got close to that because there’s still motions left over from last year,” she says. “It just seems like a very intentional thing.”

Veitch denies that the CFS tried to prevent motions from being dealt with by using any sort of filibustering.

“I think to say that there’s any intent to slow things down when our desire is to have meetings flow as efficiently as possible is not the case,” he says.

$260,000 of missing money

Delegates at the meeting were presented with a summary of the findings made by accounting and advisory firm Grant Thornton about the aforementioned unauthorized transactions in a CFS CIBC bank account. Between July 2010 and December 2014, a total of $263,052.80 in unauthorized deposits were made to this account and a total of $262,776.13 in unauthorized disbursements were made from it, going to former CFS employees, one non-CFS employee, a law firm, and a consulting company.

The account was initially set up to provide a security deposit for Travel CUTS (Canadian Universities Travel Service), a Canadian travel agency that focuses on student and youth travellers. Travel CUTS issues the International Student Identity Card, which is free for paying members of the CFS.

A history of legal battles exists between the CFS and Travel CUTS; the Canadian Federation of Students-Services (CFS-S) owned 76 percent of Travel CUTS until a private company, Merit Travel Group, purchased Travel CUTS on October 26, 2009.

$1.6 million was initially put into the account for a letter of credit; this amount was later taken out by Travel CUTS, then returned to CFS-S, with interest. Grant Thornton says in the audit that these transactions were authorized and “correspond with the details we have been given regarding the Travel CUTS security deposit.”

Two former CFS employees knew about the account. Veitch, who was not employed by the CFS when the account was created or in use, is quick to stress that the CFS no longer has any ties to those two former CFS employees. Veitch says their behaviour was carried out with a blatant disregard for the values and procedures of the CFS.

“Staff that were involved in the orchestration and in the transactions on the account are no longer employed by the federation,” says Veitch. “People that were involved in creating this account and utilizing it debased and demeaned the name and the reputation of the federation. I have no interest in defending those that were responsible.”

Veitch says the people involved were held accountable for their “reprehensible” actions and subsequently lost their jobs with the CFS.

Grant says the CFS should give members “more detailed breakdowns of where this money went” and also address further what the CFS is going to do about their budget, which was approved at the meeting and has a $1.2 -million deficit. Grant says the deficit was “normalized” during budget committee.

“A bit more information was given in this meeting about the forensic audit than we previously had, which in itself is a positive thing, but definitely not enough information,” says Grant. “If you didn’t have all the context, as most people wouldn’t—about how non-profits run, or what the actual scope of the organization is, or what kind of deficit the CFS can get away with running and still do well financially—without that context, and to just be told it’s not a big deal, why wouldn’t you trust the people at the front of the room?”

Veitch, however, says there was ample time and consideration put into the proceedings of the budget committee meeting.

“I presented the summary report. I also presented a more thorough timeline about when the account was discovered, when the forensic review was initiated and reported, in addition to some of the new financial controls that have been put in place to really safeguard ourselves from a situation like this occurring again,” says Veitch, adding that there wasn’t a lot of time for questions regarding the budget because that time was taken up by the forensic audit of the unauthorized transactions. (The CFS brought in a partner from accounting firm MNP to discuss the findings.)

Veitch says Grant Thornton couldn’t find out what happened to that money, so he doesn’t want to speculate.

“Any disbursement that lacks the proper authorization that was unreported to both the national executive and auditor of the organization is, by that fact itself, improper,” says Veitch.

The forensic review shows, among other things, a total of $89,500 taken out of the account by a former Canadian Federation of Students-Quebec employee. Veitch says he is not able to disclose the names of the former CFS employees involved in the bank account.

“Due to human resources considerations, we can’t reveal the names of former staff and officers who knew about the account and, indeed, were involved in its use. We’ve received a legal opinion to that effect,” says Veitch.

As of press time, Veitch says a lot of the reasons behind the withdrawals and deposits in the CIBC account remain unclear. As an example, a deposit in the amount of $3,000 was made from the Federation of Post-Secondary Educators of BC on November 10, 2010. (A representative from the Federation of Post-Secondary Educators of BC declined to be interviewed on the record for this story.)

“The issue is that there wasn’t documentation that established what a lot of these amounts were actually for. What you have in the report is what Grant Thornton was able to ascertain as to the purposes of them,” says Veitch.

Veitch says the account was “immediately frozen” when it was discovered by the executive at large in December of 2014, and that updates were provided to members at general meetings “every step of the way.”

“This report that you have was a product of members requesting additional details about the forensic review,” says Veitch. “The intention here is not to protect people who acted in an utterly reprehensible way. The intent here is to make sure that the federation is not putting itself in a position of legal liability.”

Unable to defederate

In other CFS news, the organization has officially recognized a petition signed by Camosun students who want to begin the process of defederation from the CFS. CFS bylaws state that students can, “by petition signed by not less than fifteen percent of the students,” vote to have a referendum, in which Camosun students could then vote on whether or not to leave the CFS. Veitch says the CFS is willing to move forward with the process, as long as the 15-percent minimum is met.

But it can only go so far, as the BCFS is withholding $200,000 of Camosun students’ CFS fees from the CFS. (The BCFS is keeping this money because the CFS also owes them money; see our cover story in our May 17, 2017 issue for more details.)

“We’re in receipt of the petition. We’re working on verifying it just to make sure that it meets the 15-percent threshold,” says Veitch. “Assuming that it’s valid, we can move forward in working with the student society to schedule a referendum date.”

That would happen in September at the earliest, because CFS bylaws prevent a referendum from taking place between April 15 and September 15, when fewer students are typically on campus. But Veitch says that a referendum cannot take place until outstanding fees are remitted.

“In order for a referendum to go forward, a student union needs to be up to date on their remittance of membership fees, and aside from the one payment of 2017 winter membership dues we are still not in receipt of membership fees from Camosun for the past two years,” he says.

The reason for that is that the CCSS has been giving Camosun students’ CFS fees to the BCFS, which is a separate legal entity from the national organization. Because the BCFS is not giving Camosun students’ fees to the CFS, the referendum will not be able to happen. (Camosun students were being told via the Camosun website that the CCSS was paying their membership fees to the CFS, not the BCFS, during those two years).

As well, the BCFS are raising their fees; the BCFS Constitutions and Bylaws, posted on their website, states: “As of January 1, 2016 the full membership fee for each member local union shall be no less than $8.76 per semester per local union individual member, pro-rated as per the practice of the member local union with regard to the levying of its local union fee.”

The policy goes on to clarify: “For member local unions holding full member status prior to January 1, 2016, the previous full membership base fee of no less than $3.00 per semester, or $6.00 per academic year, per local union individual member shall remain in full force and effect until such time as the new fee is implemented, which shall be no later than December 31, 2019.”

Camosun students currently pay $1.11 per month to the BCFS, or $4.44 per semester. A minimum of $8.76 per semester is almost double that amount. In addition, Camosun students pay $4.44 per semester to the CFS (in theory; that money hasn’t been reaching the CFS for a while now, but either way it’s out of students’ pockets).

Sources tell Nexus this raise in fees is because the BCFS claims to be doing the work of the CFS. But unless Camosun students defederate from the CFS, they will be paying both the CFS fees and the new, increased BCFS fees for the same services they’re already paying for through the CFS, effectively paying more than two times for one service. However, until the BCFS remits Camosun students’ outstanding CFS fees to the national organization, Camosun students can’t defederate from the CFS.

The BCFS did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story.

Veitch says that the BCFS raising its fees is not in dispute, as CFS member locals are allowed to do so; however, he says it’s concerning if the idea behind the 2019 deadline mentioned in the BCFS bylaws is the prediction that locals in BC will no longer be members of the national organization by then.

“If this change is being made under the assumption that students in BC won’t be a part of the CFS by 2019, it’s very presumptuous, because no referendums have yet taken place,” he says.

Veitch says that what the CFS does “is not something that is easily replicated” on a provincial scale and that it is not accurate to say that the BCFS is doing CFS work.

“The argument that the BCFS is already doing the work of the national student organization is one that I would push pack on,” he says. “We have a national lobby week every year, which brings together dozens of students from across the country. That’s not something that’s replicated in the same way in BC.”

Veitch says that this does not mean good work isn’t being done in BC at a provincial level, citing in particular the BCFS’ Adult Basic Education (ABE) campaign.

“I tip my hat to them,” he says, regarding the ABE campaign. “[But] to say that BCFS is simply doing everything that the CFS is already doing is not accurate.”

Zachariah says he hopes he can, with changes he makes, change Camosun students’ minds about defederating, but says that it’s okay to disagree.

“I would hope that it’s not too late to have a conversation to figure out a space that does work for Camosun,” he says. “That conversation looks like sitting down with their people and hearing out their concerns.”

Correction: A previous version of this story said the CFS brought in a representative from Grant Thornton to their meeting to discuss the findings of the audit, when it was in fact a representative from MNP. We apologize for the mistake.