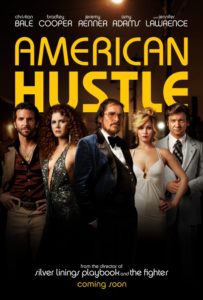

American Hustle

3/5

It’s got it all—the look, the themes, the grit, the style. It’s got the million-dollar soundtrack and the multi-million-dollar stars—beautiful stars, talented stars, stars willing to gain 40-plus pounds for their roles. It’s got the energy a period crime drama should, and more talent behind it than seems possible. But American Hustle (2013) isn’t quite as wonderful as the sum of its parts.

Usually it’s the imperfections of life that are most fulfilling—the beater car you can leave unlocked versus the $50,000 Mercedes that has you wincing on gravel driveways. Or the $100 flip-phone versus the $1,000 iPhone that you wrap in $100 of plastic to keep it safe. Each side has its own advantages, but only one side comes baggage-free; can you really enjoy something you’ve spent next month’s rent on?

American Hustle was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, but it’s loved mistakenly. It’s loved for all the reasons above and because, well, how could it not be good? Which really isn’t much of a reason at all.

You can see the film trying so hard to be clever and stylish; it charges through America’s “A Horse with No Name” and Steely Dan’s “Dirty Work” within its first 10 minutes; the dialogue is funny and quirky and subverts the “powerful man” trope; it brings in Louis CK, then ELO’s “10538 Overture,” then quickly goes to Elton John’s “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” and then semi-ironic cool slow-mo walking, Robert De Niro playing a caricature of a mobster…

However, I’ll be damned if it doesn’t work most of the time, despite its eagerness. You can criticize following up “Live and Let Die” with a second ELO tune, but can you hate it? Only in the same way you can hate a McDonald’s shake for making you fat while you guzzle down every last drop.

And so American Hustle is evidence that the Scorsese formula works, that catchy songs from the ’70s played over gunfights is just too great to not watch, and that swooping cameras and well-paid demigods are second only to, like, Snuggies and Netflix.

But what must be noted is that American Hustle is only parroting (and at times parodying) the depth of Goodfellas (1990) or the violent debauchery of Casino (1995), and that director David O. Russell is so keen on making a film that has every twist and turn planned out, as though he feels that if he lets the film out of his hands for even a second it will all come crashing down and everyone will see that it was him behind the curtain the whole time. Scorsese’s films seem to move effortlessly, as though he is merely showing us something that has been there the whole time—American Hustle is smooth too, but only because it thinks it has to be.