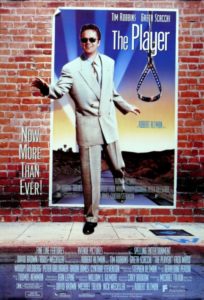

The Player

4/5

In art there exists the now-well-documented phenomenon of the “meta”: a piece of art, literature, theatre, film—anything—that is self-referential, self-conscious, about its own existence.

In the art world, there’s Andy Warhol’s pop-art “Campbell’s Soup Cans”; literature has Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote; in film, there’s Robert Altman’s The Player (1992).

But what is vital to note is that Altman, like the great artists before him, uses the meta aspect in his film not for cheap laughs or celebrity cameos but because the story needs it. Without it The Player would merely be a ’90s crime film, and not the dashingly clever, enthralling, elbow-nudging work that it is.

Like most good things, though, meta’s reputation for being edgy or clever has been severely tarnished—so much so that some would suggest meta is no more—by feckless screenwriters and directors who lean on it as a crutch and not as a device to draw the viewer in further. Examples of this include Deadpool (2016) and the abominable Sausage Party (2016), where, in absence of direction, message, ideas, and laughs, the filmmakers turned to making fun of themselves—their medium and their characters—and other celebrities, leaving the viewers asking themselves why they should bother watching a film when even its creators didn’t care about it.

The Player is much more closely related to Adaptation (2000), where the filmmaker/writer team was so full of ideas that they couldn’t help but loop the story back to their own reality—a practice that implicates the audience in a surprisingly immediate way. In that vein, The Player is so dense with references—verbal and visual—that it demands not only that you watch it multiple times, but also that you watch its influences; in doing so, you will appreciate what Altman has done with this picture.

For example, in the opening shot, the roving camera eavesdrops on a pair of men discussing the brilliance of Orson Welles’ own opening shot in Touch of Evil (1958)—an immensely complicated three-and-a-half minute virtuoso shot.

Altman then proceeds to extend his own opening shot to the eight-minute-plus range, and you can’t help but smile at its superfluousness and at its technical brilliance—and at no point does the audience feel like Altman is taking a shortcut or referencing the past because he’s out of ideas in the present.

The greatest films are the ones that feel as though they’re so full of ideas that you could watch them again and again and never quite plumb their depths—Annie Hall (1977), Being John Malkovich (1999), and Pulp Fiction (1994) are this way, so inventive that every minute with them brings something intriguing and new. These are generous films, films that are so alive they can’t help but share their idiosyncrasies with the audience.

It’s worth noting that these movies are all in the meta strain of filmmaking, with Annie Hall and Pulp Fiction drawing attention to the editing structure of films, and Being John Malkovich drawing a parallel between the voyeuristic tendencies of the cinema and spying on John Malkovich by being inside his head.

Perhaps The Player’s greatest drawback is that to really appreciate its intricacies one must be willing to do the research—to watch the films it references—and be aware of its great, winking intelligence.

This is a film made by a filmmaker about filmmakers making films. It knows what it’s doing, and all it asks is that you keep up with it.