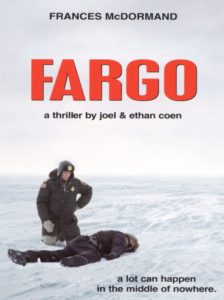

Fargo

5/5

As the thermometer scrapes zero and the ground outside crunches in the morning, dirt frozen, mud like chocolate ice; as we battle against the air on our way to work or school, feeling it searing, charring skin; during this time of stone-cold toilet seats, the panic before the car’s heating kicks in, a time when a hot coffee is more valuable than a 10-karat diamond, I turn to a film that puts these hardships in perspective: the Coen brothers’ Fargo (1996).

The poor characters in this film put up with a lot—murder, extortion, and kidnapping, to name only a few—and they put up with it all in the middle of the forbidding snow fields of Fargo, North Dakota, a place desolate as the moon, a missed spot on a whiteboard.

At the same time, these people are some of the most resilient I’ve seen—tough like the hard-packed snow they tromp upon—and it’s that quality that makes Fargo so fascinating. The characters aren’t beaten until they’re dead, never giving up—even when they should—because in their world, to give up means to be swallowed whole by the great white beast that’s beneath their feet.

And yet they’re not Tarantinian characters—they aren’t hardcore; they aren’t masters, really, of anything; they aren’t capable of blasting through a room of people, or fighting tooth-and-bone for sweet revenge; they’re just people, struggling to do the best that they can in their inhospitable world.

Indeed, each character, snow-beaten, is as fragile as a new layer of ice, with an abundance of weaknesses that serve to humanize them—something crime films often lack. Films like Snatch (2000) or the Oceans franchise are populated with characters desperate to be badass, and while it may be entertaining to watch Brad Pitt punch out a man twice his size, or to see George Clooney be devilishly clever in his various heisting capabilities, at no point are these characters real—they are caricatures of exciting people—and so it is doubly refreshing to find a film like Fargo, one deep-soaked in crime and gangster films, and yet one that possesses the same spontaneity and grit of everyday life (or as we would imagine life in Fargo would be).

With characters like Marge Gunderson (Francis McDormand)—the hero, the pregnant cop, shrewd and genial—and Carl Showalter (Steve Buscemi)—the loosely unhinged, wild-eyed small-time crook—and Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy)—the skittering, deeply panicked, insecure car salesman, who unwittingly sets the story of hardship and bumbled ideas into motion—Fargo sets out to upset the characterization norms that films of its genre fall into, and it does so spectacularly.

In this respect, Fargo is like no other film I’ve seen; it’s determined to subvert inherent tropes, and yet it doesn’t lose any momentum or get tangled and confused by the point it’s trying to make. This is a film with a pure vision, one that the filmmakers are so confident in that it’s translated with ease to viewers.

So, in these times of short days and pluming breath, I turn to Fargo because it reminds me how good I’ve got it. I sit back and admire what a wonderful, well-crafted piece of filmmaking it is while I relish the snow-free ground outside, the fact that I’ve only ever used a wood chipper for wood, and the knowledge that the Minnesotan mob is still in Minnesota. I take comfort in the fact that we are all people struggling to do the best that we can in our own inhospitable worlds.