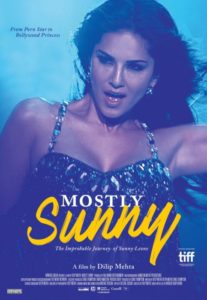

Mostly Sunny

2/5

On the surface, the documentary Mostly Sunny (2016) is about the journey that adult-film star Sunny Leone undergoes into the world of Bollywood in her attempt to branch out from her taboo genre. However, her journey is presented as one much less about spiritual or even artistic fulfillment than it is as one about the desire for, above all else, fame and fortune. The film’s unquestioning bias toward Leone renders it incapable of asking real and truthful questions, and it therefore has little more to say than one of Leone’s avid fans might.

This is unfortunate, because in the bones of Mostly Sunny is a great story—a story of family and religion, a story of rejection and acceptance, a story of the inevitable change that comes with great wealth. The film also might have touched on the cultural disparities between American and Indian lifestyles and how they—instead of her natural talent—might account for Leone’s unparalleled fame.

But instead the film is too enamoured—star-struck, even—with Leone to question why or how a Canadian-born porn star would be so accepted within Indian culture; the film is satisfied to attribute the phenomenon to Leone’s winning disposition.

Likewise, Mostly Sunny, directed by Dilip Mehta, digs no deeper into Leone’s past than to ask fairly predictable questions about her family and early life, and as a result receives fairly predictable answers in return. I got the impression, again, that Mehta was worried about prying—worried about how Leone would react were he to ask questions any more complex than the ones you might ask her at a dinner party. It’s a perverse and debilitating reluctance for any documentary filmmaker.

In lieu of asking the difficult questions about her past, Mehta opts to focus on Leone’s present, a dangerous choice, as most of her interviews are conducted with her lounging on expensive leather sofas or strolling around her LA mansion—neither of which humanize her in the slightest, but, rather, have an alienating effect on the audience. How are we meant to sympathize with such a fabulously wealthy person?

This isn’t to say that celebrities aren’t people too—but it’s the filmmaker’s job to make their lofty problems seem like our problems too. Mehta fails to do this, and as a result the film begins to slip into reality-television territory, gawking at—not analyzing—Leone’s extraordinary life.

For example, we’re taken to Leone’s hometown of Sarnia, Ontario, where we see her as a relatively normal human being. The film also shows us her life as a superstar in India, and the contrast between the two places, and the two sides of Leone, is fascinating.

However, the film makes no attempt to bring the two sides together, or to provide insight as to what the divide must be like for Leone, and therefore comes across not as an attempt to understand the star more deeply, but as a fun fact, a sound bite meant to humanize someone who’s left most of humanity behind.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997) comes to mind as a film that looks at adult-film stars and tries to understand what it is that makes them who they are. Though not a documentary, it too looks at characters that rise from humble beginnings up to the burning lights of fame and tries to understand them as people, which makes us understand them as people as well.

But perhaps Mostly Sunny never set out to be a film concerned with the truth and relatability of its message; maybe its goal was merely to point in wonderment at a shooting star, and, if that’s the case, it succeeded.