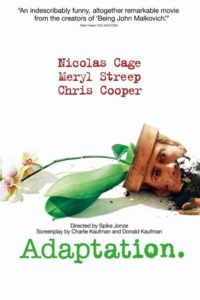

Adaptation (2002)

5/5

“Do I have an original thought in my head?”

This is the first line of the Charlie Kaufman-written, Spike Jonze-directed Adaptation (2002), and from there the film sets about exploring the depths of its own question, proving itself to be one of the most fascinating, inventive, and oddly universal plumbings of the human mind.

This is a film that is folded back on itself, and on reality, so many times that it begins to seep out of the confines of the screen until we can no longer find the beginnings or endings of what’s fictional and what’s literal. It’s electrifying.

The word “meta” is often used when attempting to pin down Adaptation, but I refrain from deploying it here because that would be to whittle the film down to a single word—one that fails to unravel any of its mysteries—and because the term is now often used as a crutch by lazy film writers who think “in” references and celebrity appearances constitute the worthwhile and intriguing insights that the films they’re making lack. One of the many things that separates Kaufman from the hacks is that he’s an overwhelmingly generous writer, and he packs his films with idiosyncrasies and seemingly needless touches that make his movies so rich and absorbing.

The other powerhouse behind Adaptation is the great Nicolas Cage, who plays twin brothers Charlie and Donald Kaufman (see, even that small whiff of a plot is already making you question things). Cage is a wildly underrated actor whose supreme talent is often overlooked, given his dodgy filmography. But in Adaptation he is outstanding, as he always is in roles that allow us to study his face and marvel at his performances that show us, wordlessly, the inside of his mind.

Jonze takes on the thankless job of directing the Kaufman screenplay (round two, after 1999’s Being John Malkovich), which puts him in a position of telling Kaufman’s story, Kaufman’s way. No director is capable of overshadowing this writer’s presence, which—in Adaptation especially—is in the very blood of the film.

What is truly remarkable about Adaptation is that it somehow is simultaneously about a single man and all of humanity. Somehow it is a critique of the film industry while also being very much a product of it. Somehow it relates its story—and its story’s story—to every living thing in the world.

Like all great films, Adaptation has such a personal and at the same time sweeping statement of humanity that—on paper—it’s hard to fully comprehend.

But as Charlie struggles with his own mind, we begin to understand how he feels, and therefore how we feel. The way Kaufman communicates this with us leaves us knowing exactly what he’s saying about himself, and about us, and we love it, and we feel heard, and we feel connected to everyone and everything.