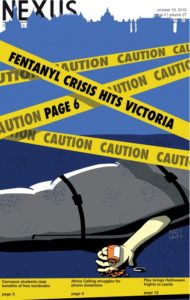

Fentanyl has killed over 200 people in BC since the beginning of 2016. Are students safe? And what is being done to stop this crisis?

A drug 50 to 100 times more toxic and potent than morphine has been causing a string of overdoses in British Columbia. Clinically, it’s prescribed for extreme pain relief in a variety of forms, from lozenges and nasal sprays to injections and pills. But now it’s being illegally sold in BC and being mixed with recreational drugs. It’s fentanyl.

The drug hit the news when Prince died of an overdose involving fentanyl in April of this year. Closer to home, there have been 238 fentanyl-detected overdoses so far in 2016 in BC alone. According to HealthLink BC, 153 people died from fentanyl-detected overdoses in 2015. As of May 31 of this year, the number of deaths increased by 230 percent, with 188 deaths already on record.

Local medical health officer Paul Hasselback says that students need to be aware of the potentially life-threatening impact fentanyl can have on students’ lives.

“I’d be really scared,” says Hasselback. “I’m not trying to scare people, I’m just trying to be realistic about what’s going on. Experimentation is actually one of my major concerns. How can we provide a safer environment? It would be nice if they don’t experiment, but experimentation will occur; it’s how do we make it safer?”

Because it’s an opioid, fentanyl increases a person’s risk of an overdose when combined with drugs like heroin or cocaine or substances like alcohol or stimulants. The BC Coroners Service found this year, in a review of toxicological findings from 207 fentanyl-detected overdose deaths in BC, that 96 percent of the deaths involved another substance. The four most frequently detected substances were cocaine, ethyl alcohol, methamphetamine, and heroin.

“We’ve also certainly got some evidence that fentanyl is being slipped into things like ecstasy, which is traditionally thought to be a stimulant for party environments,” says Hasselback. “And if there’s just enough there, that’s going to flip somebody into a more addictive lifestyle; that’s why students should be really concerned.”

It’s not just a problem for drug addicts; non-habitual users are now overdosing more frequently, as fentanyl is being put into recreational drugs. When mixed with stimulants like cocaine, it adds to the excitement factor that some people search for in mood-altering drugs. But it also increases the user’s chances of dying from an overdose.

“I think this is one of those things we need to be absolutely concerned about,” says Hasselback. “Fentanyl is not only being incorporated into heroin for people who are habitual users, but we’re seeing some of the more tragic events lately have been associated with cocaine where individuals didn’t expect they were being given any narcotics.”

A MOTHER’S TRAGIC TALE

Helen Jennens lost her first son, Rian, in August 2011 to a prescription-drug overdose. Her second son, Tyler, had been prescribed OxyContin in 2009 after a football injury and developed an opiate addiction. After Rian died in 2011, Tyler went from OxyContin to heroin because it was cheaper and more easily accessible on the street. Jennens, who lives in Kelowna, suspects that an undiagnosed case of post-traumatic stress disorder may have had something to do with his addiction.

“Tyler was a very engaging, charismatic guy,” she says. “He loved to help people; he’d do anything for anybody. He was kind and caring. And I can honestly say what happened to him in his addiction, he could not stand. He could not stand that he had become this dependent adult that had nothing left of his old life or old self. And I think that drives an addict deeper into their addiction, the self-loathing and the shame and the guilt and the remorse. And Tyler had all that; he suffered deeply. And that continues to cycle, the drug misuse. They cannot stand who they’ve become, and the only way they can is to bury it under a high.”

One day, in January of 2016, Tyler—who was living with Jennens and her husband at the time—was having a normal morning until plans fell through to go to a recovery meeting and he couldn’t get a hold of his father to borrow the car. He contacted a drug dealer.

“It was one of these dial-a-dope guys,” says Jennens. “They deliver to you. And he thought he bought heroin. He went into his ex-wife’s house—she was at work—and he went into the bathroom. And he injected a tenth of a gram, which is a point of heroin. And it was 100 percent fentanyl.”

When Tyler’s ex-wife came home from work and noticed he was in the bathroom, she thought he was taking a bath. But an hour later, she called to him; when there was no response, she contacted Jennens’ husband, who then came over. The paramedics were called, but they couldn’t start his heart. Tyler had died of a fentanyl overdose.

“So they knew what they sold him, but they didn’t tell him,” says Jennens. “You know somebody that’s using heroin would know exactly how much they can safely use. And had he known it was fentanyl, he would have never used,” says Jennens.

Jennens is a member of Moms Stop the Harm, a network of Canadian mothers who have lost children to drug misuse and now advocate for change around drug policies and human rights. Their goals are to reduce harm for people using substances and to end the war on drugs.

“We need more treatment centres and recovery beds,” says Jennens. “Naloxone [a medication that helps to decrease the effects of opioids in the event of an overodse] has to be available to everybody. We need prevention and awareness, and we need to get into the school system and explain to them what can happen and where it can lead and that drugs are not safe. They’re just not safe.”

Although she works for changes in policies that prevent the establishment of safe-injection sites, and for changes in policies and attitudes from police and the health-care system that let her down, Jennens knows that none of this can help her two boys now. But, she says, it might help another struggling family in the same position, so Jennens continues to advocate for prevention and awareness around drugs and for the people that use them. But that doesn’t always stop her pain over losing her sons.

“So how has it impacted my life? It’s horrible,” she says. “I don’t have my two sons and my grandchildren don’t have their father. And I’m sad and I’m angry and I’m really angry at the system that failed—the system that has no place to deal with this disease. My life, it can never be the same. I had two boys, and I don’t have them anymore. There’s not a day that I get up and don’t think, ‘Shit, I’ve got to do this day without those two boys.’”

CHANGE ON CAMPUS AND BEYOND

Camosun College Student Society (CCSS) external executive Rachael Grant says that the student society is hoping for awareness and safety around the fentanyl issue when it comes to Camosun students.

“I’d say that students who are out and partying might be affected, and that’s something folks should be aware of when they’re out—to be as safe as possible,” says Grant.

The CCSS has not yet taken any action to advocate or support change on campus or with the student body but is aware of the issue and how dangerous fentanyl mixed with recreational drugs can be for students.

“It is a crisis in our community and in BC overall,” says Grant, “and it’s a huge problem that’s not being addressed in all the ways it could be. And it’s very much a concern given that certain demographics are probably more affected, especially now that there’s a more recent development of fentanyl being found in recreational drugs.”

Calling for change from the provincial government, Grant wants the fentanyl issue addressed properly and with real, life-saving results. She says that the CCSS definitely feels that addressing this issue is something that the government should be prioritizing.

“For example, [BC premier] Christy Clark promised in 2013, when she ran for election, an increase in rehabilitation beds, and that reality hasn’t been seen to the amount she promised,” says Grant. “But since then things have escalated, and we’re more in a place of crisis since when that promise was made. We’d like to see our BC government supporting its community in BC more adequately because this is incredibly preventable.”

Grant says that she would like to see changes here on campus at Camosun, beginning with awareness about the subject and education around the use of illicit and dangerous drugs on campus. She feels that Camosun College should have staff prepared in the event of a fentanyl-related emergency on campus.

“We feel it would be a good idea for perhaps the college to look into having kits on campus and having folks properly trained to address an overdose should one occur, because it’s good to be prepared. So it’s something we’re concerned about, and we’d like to see steps being taken to make sure our campus is as safe as possible,” says Grant.

(Camosun College did not respond to requests to be interviewed for this story.)

BC Centre for Disease Control harm reduction lead Jane Buxton suggests using drugs with someone who is not using the same ones you are, so they can call for help in the event of an emergency. She also stresses that people need to be as safe as possible when doing drugs.

“No drug use is safe, but [they need to] make sure that there is somebody with them who can call for help, should a problem arise,” says Buxton.

In April, after the provincial health officer declared the fentanyl crisis a state of public health emergency, a higher-level task force was established by Christy Clark. The task force combines law enforcement with health officials in order to respond to overdose scenarios more efficiently, to provide information, and to better understand the problem.

“I would say it’s a more rigorous, formally structured response that has been implemented at this time,” says Hasselback. “It is focused in on making sure we get public education and information out there and naloxone even more widely distributed than it currently is. We probably have more naloxone distributed here on the island than other parts of BC.”

Safe injection or consumption sites are legally sanctioned and medically supervised areas where people can go to use drugs. There are only two in Canada; both are in Vancouver.

“There is good evidence to show that they reduce the deaths, increase the ability to connect people to services, and nobody has died while using at a safe-injection site,” says Buxton.

Hasselback agrees that safe-injection sites could help reduce the number of deaths from overdoses. Buxton says that the paperwork, time, and effort required to establish a site in Victoria—along with Bill C-2, established by our previous government—make the process very difficult.

“Looking at supervised consumption sites, we know that they reduce fatalities; that’s well proven from Vancouver and other international communities,” says Hasselback. “But we don’t have access to supervised consumption here on the island at this point. Not only does it provide a safe environment for those who choose to take a drug product, but it also provides an environment where we can begin to engage in relationships that users are more comfortable with and that may ultimately lead them to appropriate treatment services.”

According to Buxton, understanding addiction and substance-use disorders is one of the steps toward creating awareness and education in our community.

“One of the concerns is that drug use, because people don’t necessarily understand it, is highly stigmatized,” says Buxton. “So people are stigmatized, people will hide the fact that they’re using, and, hence, will use in a very unsafe manner.”

When it comes to ending this overdose crisis, there is no easy solution that will stop the overdoses quickly and efficiently. Buxton says that we have to look at it with a multifaceted approach.

“Many people and many folks who, unfortunately, are dying, it’s a mixture of groups—the people who are more experimental or occasional users, but it’s also people that have a substance-use disorder. So it has to be multifaceted. There has to be treatment available, opioid substitution therapy, supervised consumption sites, increasing access to naloxone. And increasing that awareness—although it’s been in the media a lot, some people are still not necessarily aware of their risk.”

REBRANDING DEATH

“The fundamental change is that the drug distributors are innovating,” says Hasselback. “It’s a business, and that business requires an economy; they are attracting customers and retaining customers.”

Hasselback is right: it is a business, and by mixing fentanyl in with other drugs, some drug dealers can amplify how much product they can sell by having a larger quantity but still selling it as the original drug, like heroin or ecstasy. Small doses of fentanyl can make a drug more addictive, making the recreational drug-using scene more dangerous and more captivating to first-time users.

“It makes it such that the person who is using, that might have thought they were just going to go out and have a party, are all of a sudden getting symptoms that are requiring and forcing them to come back and get more,” says Hasselback. “And that’s what I mean by the fundamental difference being the drug industry is innovating and trying to attract people. We can look at what happened with tobacco—you know, where are you trying to recruit? In this case, the main source of recruits are younger people, and those that have chronic pain.”

According to Hasselback, when someone buys drugs on the street, the quality control is never going to be the same compared to getting drugs from a pharmacy. In certain cases, the dealer they’re buying from may not even know there was fentanyl in the drugs if the fentanyl was mixed in at an early stage before they even got to the dealer.

“They may have purchased it from somebody else, and the people in the labs that are mixing these drugs, locally on the island or in BC, may actually not be all that professional,” says Hasselback. “And the base product, most of it’s coming from southeast Asia. It comes in pure, and it has to get mixed up with other drugs before it gets out on the streets. So there are lots of steps in there where mistakes can happen, where the industry can have an influence over the end user that neither the end user nor the distributors are aware of.”

PLAYING SAFE

Naloxone, also known as narcan, can save lives in the event of an overdose. When injected, naloxone can restore breathing and consciousness within three to five minutes of injection; it’s just a matter of getting the antidote into the person’s body in time. Take-home naloxone kits are now available for opioid overdoses, and increasing numbers of first responders are already carrying kits. The price range for a kit is $25 to $40, and kits are available at select pharmacies or online.

“If there’s an overdose, call 911, please,” says local medical health officer Paul Hasselback. “Get the right people in there. If you have a naloxone kit, that’s the time to use it. As soon as you identify that someone isn’t breathing, you perhaps give them a couple of breaths, give them the naloxone injection, and continue to support the breathing.”

Fentanyl can be absorbed through the skin and mucus membranes; handling the drug, or even just being around it, is a potentially dangerous act. There have been reported cases of police officers being accidentally exposed to fentanyl and needing immediate medical treatment, just from breathing in the powder or handling it incorrectly. The Vancouver Police Department has announced that its front-line officers will be carrying naloxone spray in case of exposure, and the Abbotsford Police will be equipped with naloxone kits.

As little as two milligrams of fentanyl is enough to cause an overdose and death in some adults. With the drug growing in popularity—and fatalities growing along with it—it’s important to keep the following tips in mind when using drugs:

Avoid using alone.

Try samples first.

Always have a naloxone kit ready.

Don’t mix with other substances.

Call 911 immediately if you see overdose signs in someone you’re with and be ready to administer CPR if needed.

Also, know your overdose symptoms. Overdose symptoms can include severe sleepiness, a slow heartbeat, trouble breathing, choking, gurgling, cold and clammy skin, and low, shallow breaths. Other warning signs are tiny pupils, difficulty walking or talking, seizures, vomiting, and blue extremities, fingernails, and lips.