In September, Mary Rickinson was registered to be a University Transfer student at Camosun College; she had finished her course selection and paid her fees. But Rickinson had nowhere to live. Like many students, her fingers were crossed that karma would work its magic and a place would appear, but nothing showed up. After a few weeks of long, anxious nights, Rickinson realized what her only option was: she had to withdraw from her Camosun courses and live out of a minivan with her dog and fiancé.

“There was no way that I, as a student, could afford to educate myself and to have a home,” says Rickinson. “I was fully employed while I was living in this van. It was completely not feasible to live there.”

Rickinson and her fiancé made the decision to move to the Comox Valley and attend North Island College. To put it in the simplest terms possible: Victoria’s housing market pushed Rickinson right out of Camosun; Camosun lost a student because of the housing market.

Making freedom out of chaos

Rickinson describes the process of trying to find a place to rent in Victoria as being “incredibly disheartening.” She says she tried continuously, for months, with no success. So she lived in her van.

“Camping in a van for the summer is fine. It’s an adventure. But trying to educate yourself in a van is absurd. Victoria does not have a housing strategy yet. It’s clear that one is desperately needed.”

As one measure to try to improve the housing situation in town, the City of Victoria is thinking of removing the minimum square footage requirement to decrease costs. Rickinson says that “putting people in cages” is not the answer, and going lower than the 355-square-foot minimum is pushing it.

“I believe the quote that [Victoria mayor] Lisa Helps used was it’s ‘low-hanging fruit’. It’s not even fruit,” says Rickinson. “You’re talking about putting people in, essentially, cages. How is a human supposed to comfortably survive in less than 355 square feet?”

Rickinson says that the 15 percent Foreign Home Buyer’s tax that Metro Vancouver put into effect didn’t help matters; she says it actually made it worse for people trying to rent in Victoria because Vancouver buyers set their sights on the island.

“It was already hard, but after Vancouver put in that 15 percent… there were bidding wars on apartments that we had scheduled interviews on and couldn’t even get to because the first few people that had seen it started to bid against each other for monthly rent.”

She says that for students, the issue of housing is directly related to all other aspects of life, including school.

“If your housing isn’t secure, there’s no way that your food is secure, there’s no way that your education is secure,” she says. “It’s all intertwined.”

Rickinson says that Camosun has been discussing building residential units at Interurban for years, and that if that’s what it takes for some students to have food and educational security, so be it.

“There’s no reason why the students shouldn’t have safe housing. I couldn’t even imagine my course load in a van in the rain with a dog and a fiancé,” she says. “That’s crazy.”

Commutin’ for Camosun

If you’re not a morning person, don’t even think about complaining about an 8:30 am class to Camosun first-year Psychology student Ricardo Hardin, who lives in Chemainus. Hardin rises each day at 4 am to catch the number 66 bus from Duncan to make it to his morning class on time. He says he’s exhausted at the end of each day and does his homework on the bus ride back so he can fall into a slumber when he gets home.

“At the end of the day, I’m tired; I’m exhausted,” he says. “I stay at my friend’s house in Victoria maybe once a week, and that’s a help, but I want to be here [in Victoria]. The living situation here is so hard.”

Hardin adds that he is debating taking out a loan for a house in Victoria, just so “I can have money right in my hand the second I see a spot that’s open, so I could pounce on it. And that’s stressful, man.”

Hardin’s education at Camosun is paid for by a sponsor; he says that living in Chemainus is “the only really affordable option” because the thought of having to pay for a car—after insurance, gas, and upkeep— is a scary one. But commuting over the Malahat day in and day out on public transit is taking its toll, he says.

“It’s hard to take the bus, and I want to live here,” he says. “At the same time, it’s so stressful to meet up with my expectations for my [First Nations] band of having good grades.”

Hardin says that the main things his housing problems have taken away are freedom, a sense of independence, and any hopes of having energy for anything besides getting to and from Camosun.

“It’s not my main priority to have a little bit of free time, but I just like to be a little independent once in a while and not have to work around the schedule of everybody else,” he says. “For me, it’s a real struggle to get from here to there; it’s been a mission, and it’s taught me a lot about how to keep my priorities straight. But it’s really bringing me down.”

Hardin says that banks and foreign investors play a big role in the housing crisis and points out that everybody, no matter their socioeconomic status, is impacted by what’s happening.

“I would consider everybody affected,” he says, “even up to the people who are just graduating out of this college. It’s a really big problem for Victoria and Vancouver right now.”

Hardin says that he wants Camosun students to know they are not alone if they are feeling “out of sorts” on how they are going to “make it to their next year in college.”

“I see a lot of the stress in all the other students as well, just in their own schedule going back and forth, even if it may not be getting up at four o’clock in the morning.”

Hardin says that he’s not the only Camosun student who takes the number 66 bus from Duncan every morning. He feels Camosun should have some sort of student housing setup, which he says would be an investment.

“Even if they didn’t have their own building for residency, maybe they could partner with some local building to help students coming in and out of there.”

Hardin says he has seen places that are completely vacant, and he thinks that would be a perfect opportunity.

“Prices are too high,” he says. “Nobody can afford them. Even if they are in an all-right area of town it’s still just a little too high for most people to afford.”

Too much isn’t enough

Students are no strangers to working around the clock. But Camosun first-year pre-social work student Mellissa Pelletier nearly worked herself into the grave—literally.

Before she started at the college, Pelletier was working 90 hours a week while homeless and living out of a backpack; she developed severe abdominal pains and was ordered to stay on bed rest by doctors. The pains—which she says were purely stress-induced due to working so much and having no place to live—went away in time, but not before she hit rock bottom, both physically and psychologically.

“I filled a hiking backpack with all the necessities of life and basically spent the next three months couch-surfing between friends’ houses while looking for a place to live,” she says.

Pelletier says that her head space at the time made things harder, and so did the actions of a former roommate.

“It was very stressful; it was very scary,” she says. “I had just moved out of my parents’ house, and my roommate was just not a very good person,” she says.

The roommate in question? Pelletier says he informed her in the last week of February that he was moving out in seven days. Even working 90 hours a week, she says she couldn’t afford to live where she was without the financial help of living with someone.

“It caught me, obviously, very off guard, and while working 90 hours a week, it made it very difficult,” she says. “I was quite stressed, and I actually ended up getting really sick. I was in and out of the hospital while trying to work 90 hours a week.”

The sickness wasn’t purely physical. Pelletier used the government resource Plan G, which allowed her to get medication for her mental health—which she says was strained by homelessness—covered.

“It was just the stress of working like crazy and not having a house,” she says, “so I never really had my own space; I never had time to de-escalate.”

Pelletier says that one of the biggest underlying problems of the housing crisis for her is the quality of the few places that are available. Living in a house where, as she puts it, “in the wintertime, the wind would blow and your hair would move in the living room,” is not a problem a hard-working citizen should have, she says. It wasn’t so much that she didn’t have the money, but that all the options available involved her living with a bunch of men she didn’t know, which she says speaks volumes about the calibre of the housing crisis.

“I could afford a house, but it was a matter of finding one,” she says. “The spaces that were open would be, like, me moving in with a group of three dudes.”

She says that one of the keys for her was accepting help from friends who offered their couches.

“It’s really hard because you definitely feel like you are failing as an adult,” she says. “Especially when you’re that young and it’s your first try.”

Pelletier stresses that it is rarely a person’s fault if they find themselves in that situation, pointing to Victoria’s notorious vacancy rate.

“Then, if you count in the fact that most young people are on a strict budget, and they’re still trying to figure out so much about themselves,” she says, “it just makes it very difficult.”

Pelletier says that putting student housing on campus would help a little, but that it wouldn’t do much to fix the bigger scope of the problem.

“There’s just not enough [houses] in general and the pricing is absolutely ridiculous. I think it would be nice if there was some kind of system in place to protect students.”

Political gridlock

Camosun College Student Society (CCSS) external executive Rachael Grant says that lack of campus housing is definitely an issue and adds that Camosun would put money toward that sort of thing if they could.

“That’s been something that our government hasn’t prioritized since the early ’60s, establishing student housing on campus in the form of residences; there’s also an issue in that the government currently restricts institutions like Camosun being able to borrow money. So the college is in a weird place where they can’t borrow money, and because [housing is] very expensive, that’s not something they can just absorb, cost-wise.”

Grant says that because of government policy, Camosun’s only option is a public-private partnership, which she says is not something the college is going do any time soon.

“Those are a problem because it leaves them in a space where the college doesn’t have a lot of say over how that building would be run. Often, in those types of situations, the cost of living there is very high for students and doesn’t actually create any form of revenue for the institution itself.”

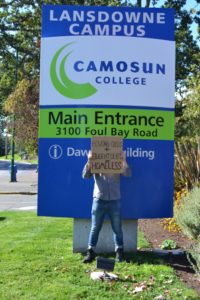

(The Alliance of BC Students, which Camosun students are not members of, organized a protest in Victoria on Tuesday, September 27 to try to raise awareness of the situation regarding government getting in the way of post-secondary institutions building student housing.)

Grant says the issue that really needs addressing is the lack of affordable housing; she says what the CCSS would like to see the government do is “either give funding so residences on campus can be built, or remove the restriction on institutions like Camosun to be able to borrow money, because if the college was able to borrow money, they would do that.”

BC Housing is a government agency that provides assistance to renters in the form of subsidies and subsidized housing. A BC Housing spokesperson offered the following comment via email:

“BC Housing is willing to work with post-secondary institutions and would consider proposals for affordable rental housing geared to students. We may also consider incorporating student housing into existing affordable rental housing buildings within appropriate distance to post-secondary institutions. Students can apply to BC Housing for affordable rental housing units. We will evaluate each application based on eligibility requirements, which includes age, income, and how much financial support the individual receives.”

A public policy issue

As the CCSS’ Grant says, the on-campus housing issue for students comes down to the government all but putting a brick wall between Camosun residences and homeless students. Rickinson says that Camosun, as a whole, seems “very aware of their students’ needs.”

“I don’t think the actual institution of Camosun College is deaf,” says Rickinson. “They do what they can with restrictions at every corner. The government is deaf to everyone’s needs but their own. I don’t believe that they have the pulse, at all, on the working-class British Columbian, or the low-income British Columbian, which is what our province primarily is.”

Rickinson says that she has not seen a government, except for a brief NDP stint, attend to the needs of younger or working-class people.

“I’ve heard a bunch of rhetoric, and I’ve heard a bunch of lies, but haven’t heard anything that translated into services,” she says.

Rickinson believes that the entire province needs to implement “a 15 percent home buyer’s tax” to keep the province in such a place where the safety of its citizens is addressed in terms of shelter.

“We’ve seen an immediate alleviation of the housing crisis in Vancouver since that tax was in place, but now those buyers who are looking for investments are going to go everywhere else they can. It was just a shift of the problem, and if it isn’t dealt with en masse,” she says, “it’s not going to improve.”