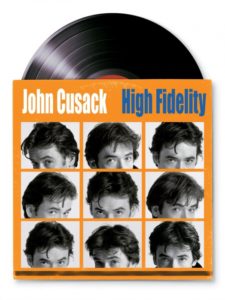

High Fidelity

5/5

High Fidelity (2000) is a rom-com in all the right ways. It’s a movie that knows how people work and what motivates them; it knows that people aren’t perfect, and it works with that fact.

The humour in the film is paramount, and it’s not the kind that you’ll find in most rom-coms today; it’s subtle, keenly observed, and poignant, and it comes across as effortless in the hands of John Cusack, Jack Black, Iben Hjejle, and Tim Robbins.

With humour, the film acts as a meditation on the intricacies of adult life, and how adult life at times can seem so similar to childhood. The film follows Rob (played by Cusack), the doggedly neurotic, unkempt music-aficionado hero, during a life crisis involving a “what-does-it-all-mean?” journey through each of his past relationships. Why did they go wrong? Whose fault was it? Who among the exes are faring adult life best? Y’know, the important stuff.

However, the essence of this film is not in the plot; it’s in the relationships between people. The film deals with the little details that make all the difference: the inflection of a certain phrase, or someone’s choice of words, or the treachery of seemingly innocuous actions. The film notices these things and presents them in funny, intelligent, and emotional ways.

Another part of High Fidelity’s success is its loyalty to the Nick Hornby novel it was adapted from. Far too many movies merely take the idea of a novel and run from there, losing the charm that the story once had in the process. However, under Stephen Frears’ direction, High Fidelity maintains and enhances the original novel by working for it, rather than merely with it.

Cusack’s version of Rob is just as well done; he literally and figuratively pulls on the shlubby jeans, old Pretenders T-shirt, and beat-up messenger bag of a thirty-something manchild and steps confidently into the role of a character so very unconfident in himself.

The key to this film, though, is that it approaches subjects like aging, loneliness, and unhappiness with realistic humour. No jokes are forced, and we find ourselves laughing mainly because we relate to the plights of the characters. Ultimately, High Fidelity is wonderful because of that relatability; we feel as though we know the people not only as characters in a film but also as people from our own lives.

The goal of a movie should be to touch the audience in some way—to answer their unasked questions—and leave them feeling understood; only films as sharp and funny as High Fidelity, that understand so well the irrational idiosyncratic human psyche, are able to do that.