Joseph Mitchell was one of the greatest long-form magazine writers to ever work for The New Yorker, one of the greatest publishers of the genre.

Despite that, today he is almost as famous for what he ended up not writing: Mitchell suffered a 30-year writer’s block at the end of his career, and although he showed up for work every day from 1964 to just before his death at age 87 in 1996, he didn’t publish a single story in that time.

After joining The New Yorker staff in 1938, Mitchell quickly became known for his insightful, compassionate, and vivid portraits of hobos, fishmongers, gypsies, restaurateurs, shopkeepers, and barkeeps. The working class, the down and out, and especially the eccentric: these were the heroes of Mitchell’s reportage. His stories were often tinged with nostalgia for the better days before the increasingly bureaucratic world of post-war America. He wrote with sadness about restaurants, bars, and people who were forced to lose their essential characters in the process of modernization.

Mitchell became known for “an offhand perfection of style”: his stories flow so naturally the writing seems almost casual, and yet they are the result of a meticulous craftsmanship.

But his style as a journalist didn’t come without controversy. Several of his “portraits” turned out to be conglomerates of many different people, and he never shied away from a generous creative license when it came to developing characters through their dialogue. It’s what makes his stories so compelling, what makes his portraits seem so vivid and real, but it would not stand up for a moment to today’s strict journalistic standards.

Explanations for the long silence at the end of Mitchell’s career range from the weight of success to depression. But I wonder if it didn’t have something to do with Mitchell’s own essential character, and a fear of what might be lost in the process of keeping up with the times.

Joseph Mitchell must-read:

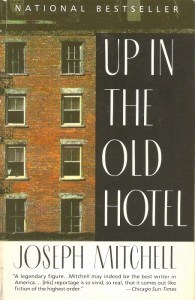

Up in the Old Hotel, and Other Stories

(Public Library Oak Bay Branch: Paperback Fiction)