“I am not meant to be alone and without you who understands,” wrote John Singer, a deaf mute who is at the center of Carson McCullers’ beautiful novel The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.

Set in the depression-era south, the novel follows the lives of several townspeople who revolve around the mild-mannered Singer, each driven, by a unique loneliness, to seek his friendship and share their troubles with him.

Pushed to the outside of society, they all deal with isolation differently. Dr. Copeland, an educated black man, dreams of a “strong, true purpose” for his race while estranging himself from his family. Jake Blount, a frustrated labour organizer, is a self-destructive alcoholic whose rants slip often into mad ravings. And Singer walks alone at night; in his face “there came to be a brooding peace that is seen most often in the faces of the very sorrowful or the very wise.”

The misanthropic loneliness of the adults is contrasted by 14-year-old Mick Kelly, McCullers’ semi-autobiographical stand-in. A clever, energetic tomboy, Mick retreats from the confusion of the world by going into what she calls her “inside room,” the place in her mind where she can be alone with her aspirations and her secret dreams.

The book is as much about the condition of isolation as it is about the power we can find when we embrace loneliness and find ourselves, alone, in the center of our selves. It is from her inside room that Kelly looks out and finds the strength to dream up a better world than the one in which she lives.

Aloneness and isolation are a part of the human condition, McCullers’ characters seem to say, but it is how we deal with our loneliness that counts. She gives us different visions of what embracing the solitude at our centre might look like, but in the end she leaves it up to us to choose which vision we will embrace for ourselves.

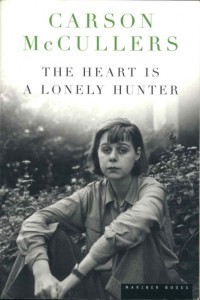

Carson McCullers must-read:

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

(Public Library: Esquimalt Branch, paperback fiction)