I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the documentation of various forms of hard rock and heavy metal. It sounds wildly specific, but it’s become a passion of mine to document bands and eras of times past to make sure their significance is not forgotten. I’ve done it in my writing, I’m working on a documentary film about a specific record label, and I just think about this stuff a lot while I’m walking from point A to point B.

Across all genres of music there are people working hard to document very specific eras and subgenres within hard rock, trying to preserve them for the ages. We tracked down an American diligently documenting the history of one subgenre of extreme metal and a local who is making sure that early Canadian hard rock records are staying in print.

It’s not glamorous work, and it’s certainly not going to pay the rent; most months it probably won’t even pay the bills. Heck, let’s be honest: people doing this are often losing money in the process. But it’s a labour of love, because for those doing this work, the burning desire to make sure these musicians are remembered comes before anything else.

Echoes from decades past

Here in Victoria, Jason Flower releases archival recordings from very early proto-metal and hard rock bands from Canada (and beyond—he’s received a grant to document the history of post-World War II contemporary music in the Republic of Georgia) on his Supreme Echo record label. Flower—who has been actively involved in the music scene for much of his life, as a musician, recording engineer, record label owner, and other various music-related pursuits—has issued archival recordings by bands like early Canadian metal act Triton Warrior and proto-black metal/power-poppers (!) Twitch.

“It’s important to me to see historically innovative musicians documented and recognized for their achievements,” says Flower. “I see it as ethnomusicology and to contribute to the documentation of seminal arts movements, retrospectively underlining their cultural relevance.”

Flower, who also runs the Supreme Echo record store on the corner of Government and Bay, says that his aim is to promote interculturalism and counterculture, “because the world’s mainstream art milestones are often an appropriation of their true origins.” And he does this through his work, which, he’ll be quick to point out, is more focused on archival work than reissues.

“Reissues are easy to do in comparison with a documentation of something that should have been but never was,” he says. “There’s a meticulous knack for detail required; you must find the truth within multiple interpretations of the past, hunt down long-lost audio and imagery, and be as neutral as possible to present something just as it was when it existed.”

With all his archival work, sometimes taking massive amounts of time, energy, and money to put together, it’s easy to think that Flower is living in the past, something that he acknowledges can get a bit odd at times.

“I suppose it can get weird trying to dig back 40 years and write out a clear oral history while filtering out ego and imagination of aging musicians,” he says. “Often people are looking back on a high point of their lives, and occasionally there are bad memories, too.”

Ken Ambrose played drums for Triton Warrior, whose 7” of 1972 recordings Flower released on Supreme Echo. Ambrose admits that he “just wasn’t interested” in Flower’s initial offers to reissue the record “many many years ago.”

“I had no idea who he was and why he wanted to get involved,” says Ambrose, “but due to his years of persistent contact I finally sent him one of my last records that I had saved. To my surprise, he’s put in countless hours and research to verify every last detail.”

But despite his initial reluctance, Ambrose is very pleased with the end result of Flower’s work. He says it’s a “better package” than the original release from back in the ’70s.

“It’s brought life to a record that was already in the grave and made it better,” he says. “Jason worked non-stop to achieve this result. The band is so grateful, and it’s a souvenir for my daughter to have as a keepsake. Bravo, Jason.”

Only death remains

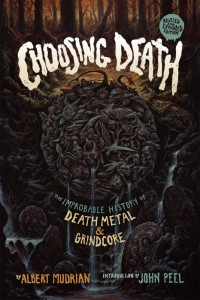

Meanwhile, over in Philadelphia, Albert Mudrian is hard at work juggling many different projects involving extreme metal. When I give him a call he’s dealing with his normal duties as editor-in-chief of Decibel magazine, North America’s only remaining monthly heavy metal mag, and he’s also ironing out last-minute details for Decibel’s annual tour and preparing for the release of the expanded re-release of his 2004 book Choosing Death, which documents the origins and history of death metal and grindcore.

“The impetus for doing the original version was just making sure that those bands, that their importance wasn’t lost,” he says of his book. “I never imagined there would be not only a recognition of how important they are, but a celebration, really, of it, which continues to this day.”

The celebration that Mudrian speaks of involves legendary death metal bands like Carcass and At the Gates (the latter of which headlined this year’s Decibel tour) reuniting, performing, and recording new albums, sometimes to more acclaim now than they received during their initial run. This changing face of death metal is something that Mudrian wanted to address in an expanded edition of his book. But he says his motivations for writing (and re-writing) Choosing Death are pretty simple.

“I’m a fan, ultimately, at the end of the day,” he says. “For me, it was definitely not out of any motivation other than, man, I love this stuff and want to make sure that people know where this stuff came from.”

Mudrian knows one of the potential pitfalls of doing this kind of music documentation is having a fan’s perspective and falling down a rabbit hole of outrageous minutiae that only the most severe obsessive followers would care about.

“You can go as deep as you want,” he says. “It comes down to how much can you handle and then how much of this can you include while maintaining some kind of cohesive story, not losing focus or flying off on too many tangents.”

Mudrian’s been working on the reworked version of his book for around a year. While that seems like a long time to be working on a project that is, primarily, focused on the past, he says that living in the past isn’t really a worry for him.

“No, not really,” he says. “I hadn’t really started Decibel yet when I first started writing Choosing Death. It might have been harder if I started Choosing Death right after I started Decibel, then it’d be like, ‘Where am I? Am I looking forward? Am I looking back?’ But to me it didn’t seem like that it was necessarily a bad thing.”

For the fan in Mudrian, the process of interviewing the bands he talked to for his book was certainly not a bad thing. He describes the interviews as being “super exciting” and a huge learning process for him.

“When that process began of doing those interviews, it was great for me,” he says. “I’d get off the phone with somebody, and 80 percent of the conversation were just things that I had no idea that’s how they happened. I was a pretty big fan of this stuff growing up, so that’s when I knew that this was something cool, this is a story that hasn’t been told, this is going to have information that people can sit down and really get into and learn about it.”

One of the bands featured in Choosing Death is Cretin, a grindcore-leaning death metal group from California. Marissa Martinez-Hoadley is the band’s guitarist/vocalist, and she says that because she’s excited by this music and its history, she’s excited by anything that accurately tells its story.

“The music appeals to a very small segment of society, so I imagine that the book’s overall significance is pretty minor,” she says. “But, it’s a great resource for those of us who are into the music, whether to reminisce on ‘the good ol’ days,’ or for those who are new to grind to learn about the past.”

A couple weeks after I interviewed Mudrian, we had an email exchange chuckling over a double-CD reissue collection of demos and rehearsal tapes from an obscure extreme metal band from years past who, even back in the day, weren’t met with much regard. The record label reissuing the collection referred to it as “essential,” which touched on something Mudrian said to me: it’s important to remember that not everything is classic just because it’s old. Just as they do today, some bands sucked then, too. We had a quick laugh over the absurdity of it and went back to our days.

Of course, immediately following our email exchange I went and got the collection; even if I never listen to it, it’s filed away in my own personal collection, one more piece of weird-rock history documented, for better or for worse. I couldn’t resist. I wouldn’t be surprised if Mudrian did the same, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Flower mentioned this exact collection the next time we chat. The archivists never stop archiving; the documentarians never stop documenting.