“The most essential gift for a good writer is a built-in, shockproof shit detector.”

This statement is typical of Ernest Hemingway, who was almost as famous for his bravado lifestyle as for changing the course of modern literature.

Born in 1899, Hemingway killed himself in 1961 after inventing a whole new way of writing fiction. His influence on subsequent generations was so great that American novelist Norman Mailer joked, “I almost wouldn’t trust a young novelist who doesn’t imitate Hemingway in his youth.”

His style, famous for its short, declarative sentences, won him the Nobel Prize in 1954. The settings of his stories and novels were often taken from personal experience: deep-sea fishing, driving an ambulance in WWI, reporting on the Spanish Civil War, and watching bullfighting, for example.

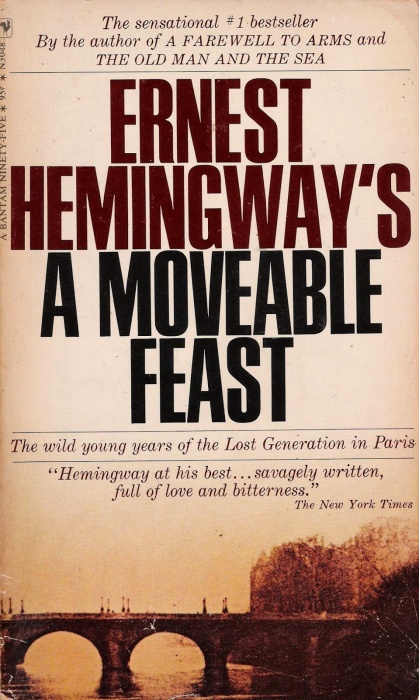

A Moveable Feast, his literary memoir about hobnobbing with Gertrude Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald in Paris in the ’20s, is a classic of bohemian literature.

Hemingway’s clear and simple writing is what makes him so enjoyable as a storyteller. His worlds are instantly familiar, his characters all true to life.

But the simplicity of the writing is deceptive.

Hemingway’s genius was not in what he included, although each word was meticulously chosen to create the “truest” image. It shows in what he left out.

“Anything you can omit that you know, you will still have in the writing and its quality will show,” he wrote.

This addition by subtraction, strengthening the narrative by allowing readers to fill in with parts of their own experience, has come to be called the Iceberg Theory of composition.

“The dignity of movement of an iceberg,” wrote Hemingway, “is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.”

Hemingway’s apparently simple descriptions give evidence of a richness of plot, character, and thought lurking just below the page.

Hemingway must-read: A Moveable Feast (Lansdowne library code: PS 3515 E37 Z475).