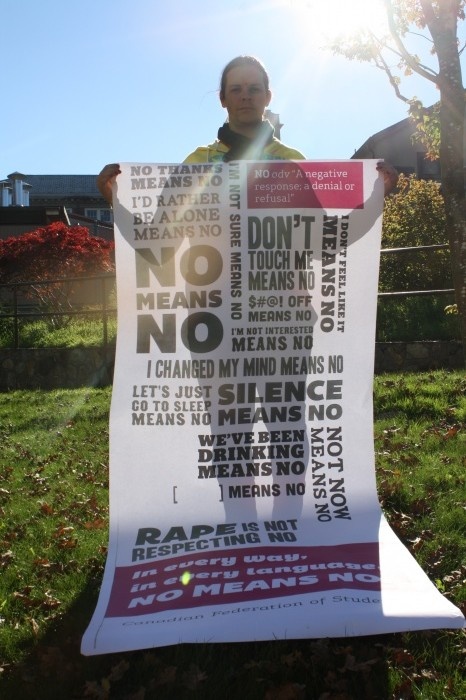

The Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) has re-launched their longstanding No Means No anti-sexual assault campaign. According to the CFS, in the wake of rape chants happening during frosh week at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and Saint Mary’s University, as well as three recent reports of sexual assault at UBC, awareness is needed now more than ever.

“There is a culture of silence around this culture of violence,” says Madeline Keller-MacLeod, CFS-BC women’s liaison and Lansdowne executive for the Camosun College Student Society (CCSS). “I think the chants are kind of a reflection of what our broader society is willing to accept right now, and No Means No is saying that we need to change that, and it is our responsibility to change that.”

The campaign, originally launched by the CFS in 1992, was intended to combat sexual assault on campus and in communities nationwide. Some studies say that only eight percent of victims of sexual assault come forward to report the crimes, and the CFS claims there has been no significant decline in sexual assaults over the past 20 years.

One of the primary focuses of the re-launch revolves around the idea of consent, says Keller-MacLeod.

“No can take many forms and each of those forms has to be respected,” she says.

Daphne Shaed, CCSS women’s director, explains that consent is a communicative process and that silence is not consent. She also points out that the word “no” is not negotiable and that any consent given has a limited life span.

“Consent is not something that is carried forward to any other situation than the immediate, present moment that you’re in,” says Shaed. “To carry forward regardless of consent just because you feel that you’ve reached a point of no return is ridiculous. There is no point of no return.”

The campaign is also addressing the validity of consent in certain situations.

“When someone has consumed alcohol or drugs, for example,” explains Judith Prat, manager of direct client services of the Victoria Sexual Assault Centre, “they’re not in a cognitive state where they can logically give consent. Their judgement is clouded.”

Prat says she likes the campaign but would like to see more emphasis on the the legalities involved.Sexual assault is a criminal offence prosecuted under the Criminal Code of Canada.

“Education is excellent,” says Prat. “I like the positive messages in the campaign, but I would also like to see more reference to the criminal codes in the posters.”

One of the other goals of the No Means No campaign is to educate would-be perpetrators in hopes of getting them to recognize their role in the dimensions of sexual assault or rape; according to Keller-MacLeod, it also points out the fallacious logic of victim blaming.

“Rape and gender violence is about power, not sexual gratification,” says Keller-MacLeod. “It doesn’t matter what you’re wearing; it’s still considered something you should be afraid of.”

The campaign also discusses the changes in rape culture over the past 20 years and how it has unfortunately become more a part of our everyday vocabulary, says Shaed.

“I don’t think in 1996 you would have heard people talking about conquering something, or dominating something, or doing well in something, in relation to rape,” she says.

Keller-MacLeod says she has heard firsthand how words can be used to further rape culture on campus. “I heard somebody come down the stairs of Fisher Building one day and say they had just ‘raped that test.’ Part of rape culture is refusing to stand up against sexualized violence, and even just comments, comments that you can say are benign.”

The CFS and the CCSS are organizing several workshops in the winter semester highlighting topics such as what consent really means; the nature of this temporal arrangement; how to ask for consent; nonverbal communication; methods of de-escalation and avoidance; empowerment for women; and self-defence. Also, this semester, keep your eyes open for a poetry slam around gender violence in early December.