Whenever I read the next great mental-health study or report, I’m reminded of a scene in The Life of Brian. Brian is about to be crucified, propelling lover Judith into action. She charges into their Judean rebel group’s board meeting, shouting, “Do something!”

The president, Reg, played to perfection by John Cleese, nods enthusiastically and excitedly assures her, “Yes! Right.” He pulls up a chair, “This calls for immediate discussion!”

Let’s discuss it, that way we don’t have to actually do anything. But many have found a way to both work and speak on behalf of the miserable invisible. Visionaries who believe we can overcome poverty, and work for change. They are the executive directors of non-profit organizations (NPOs) who head an army that has spread a net of compassion over humanity.

NPOs benefit society by upholding democracy, ensuring hope, and giving a voice to those in the gaps. They hold community together through volunteers and donors, and inclusion of workers. They see people pre- and post-system involvement as well as during it, even as they too are part of that same system, but are not fully funded as many assume. They are driven by the need they see.

So, what keeps our non-profit leaders hanging in there in the face of legendary bureaucratic obstruction? Many are frustrated by the equation of time fundraising equalling less time providing service. How do they sustain their remarkably positive attitudes?

Similarly to Judith’s plight, we can compare the non-profit effectiveness to the infuriating delays caused by ordering studies. Historically undervalued and under-funded, these bloodlines of our nation have even had to hold their tongues to avoid having their funding cut off.

Meeting of the minds

It’s Thursday. I’m seated at a makeshift boardroom table in a small back boardroom with other directors from Victoria’s not-for-profit sector, my eyes stinging pleasantly on the coffee dust from nearby Cafe Fantastico. As the social problems of our city settle on the intelligent, concerned faces around me, we get down to business.

The Progressive Recovery Group (PRG) is a collective that welcomes agency reps, initiative reps and guests. Chaired by Hazel Meredith, executive director for the BC Schizophrenia Society in Victoria, the PRG was created by Meredith in 2006, along with Liam McInery, then executive director of the Capital Mental Health Association (CMHA).

The PRG describes itself as being “developed to address concerns about fragmented service delivery in the mental-heath and addiction system.” Attending a PRG meeting is a lot like giving oneself not-for-profit oxygen once a month.

It’s a good idea to hold onto something solid when entering Meredith’s orbit. During our interview, she spoke calmly, fielded phone calls, and lobbed decisions through her office door to colleagues in the hall.

Her black, executive outfit provided an anchor for a head of gorgeously thick, curving gold hair that has a personality as lively as its owner. And she too has a mental-health story to tell. Depression stalked her family, and she lost two family members to suicide. Beginning in Manitoba, in her 18 years in the field Meredith has garnered expertise on every side of the problem. She describes her move to the coast ruefully: “In my experience, Manitoba uses more strength-based recovery oriented based modelsŃnot so much here in BC.”

As for her involvement with the PRG, she believes the collaborative model has been useful locally, and will eventually see the same success as the Supported Employment Network in Manitoba. I ask her what her wish list might include.

“I’d like to see peer individuals train as leaders, with an emphasis on health, recovery, and wellness planning,” she says. “We want to make sure when someone reaches their hand out in hope, someone is there to grasp it.”

Giving back

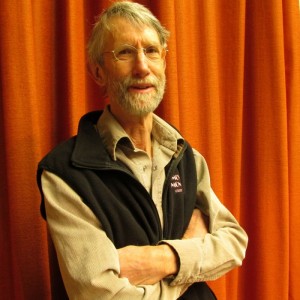

One of the people at the NPO table is Bruce Saunders, the quiet force behind Victoria’s iconic Movie Monday theatre. Saunders reminds me of Bob Dylan’s laid-back intensity in a lanky Jimmie Stewart-esque body. In 1993, he discovered a potential movie theatre in the old Eric Martin Pavilion near the Royal Jubilee Hospital. The venue caught his imagination in that visionary way of many non-profit leaders. Movie Monday has become a staple of moviegoers in this city, and recognized by the provincial Ministry of Health as a mental health Best Practice.

Saunders begins our interview by quietly telling me a story he’d told many times before.

“I’ve lost a sister to suicide, and I’ve been hospitalized; so has my mother.”

Like so many others, it’s his personal experience that drives him to do this work. He’s also facilitator of and a participant in the Mood Disorders Association (MDA) of BC, a local support group. The MDA has been peer-run for 25 years, building community where there used to be only isolation.

He says he’s luckier than others because he has pretty much complete control. “The bureaucracy that defeats many initiatives cannot bog mine down.”

Saunders says he has created a perfect balance between the physical nature of his landscaping business, the emotional connection of his non-profit work, and his strong ties to his family. But there’s another element he suggests is key to recovery.

“Helping others is part of the cure,” he says. “I’ve seen the delicate nature of recovery and believe it is possible, and that gives me immense optimism for others. Peer support works and is cost effective. Through helping others, a person realizes that the potential of recovery is there.”

Redefining charity

Across town, I meet with Jane Arnott, executive co-director of the reinvented NEED2: Suicide Prevention Education and Support. Small, grey-haired, and neatly dressed in blue and violet, she produces an immediately calming effect. My guess is there have been many who underestimated the fierce heart behind the gentle demeanor.

In 2010, when the province transferred the crisis line element and most of their funding to a Nanaimo group, NEED scrambled to hold on to what was left. With everyone pulling hard for the next two years, they became NEED2. Cheerful, in spite of it all, Arnott quips that they “are a brand new organization with 40 years of history.”

She goes on to say the “sector” isn’t understood, and gives me a quick history lesson on the non-profit movement. Many NPOs have their roots in the ’70s when groups beyond the churches were beginning to form in the community and provide services outside the sphere of churches or other state institutions. She notes the change came with redefining the word “charity.”

“We don’t tend to use the old charity modelŃit reinforces inequality,” explains Arnott. “There’s no mystery to our success in the ’70sŃit was the product of a lot of social activism. We were using the concept of change agency, and we were starting from scratch then too, with no manual to do things.”

She remarks wryly that the funding hoops “waste valuable energy that could be better applied to direct community work.”

So why does Arnott stay in the fight, after all that she’s been through?

“My values are strongly rooted in the belief that communities are richly resourced and have the capacity to come together over the issues they face. But the other piece for me personally is I have a responsibility to give back, it is something we need to do.”

And she has a message for those of us who have answered the calling.

“When you think you still have something to offer, even if all you’ve worked for is lost, believe in your vision,” she says. “It might take a while, but there will always be others who will get together, now or at some point in the future, to do something about community need.”

If our governments want to apply pressure to the flow of money gushing from the artery of health care, they’d do well to better support to the non-profit organizations.

But the first step, as anyone in recovery will tell you, is admitting they have a problem.