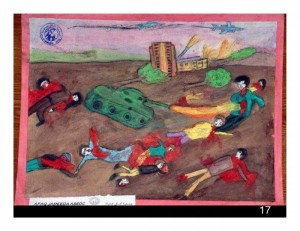

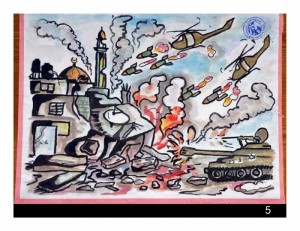

Imagine a childhood where you fall asleep every night wondering if you’ll wake up alive, praying that your home will not be targeted, and fearing what you’ll have to face the next day. Imagine waking up every morning and looking out your window to see dead bodies, bullets flying, bombs in the air, and looks of distress everywhere. These are the thoughts and worries that go through the minds of children in conflict areas almost every day.

Children in Gaza know all about being caught in the middle of a warzone. And now their images are available for all to see in the art exhibit A Child’s View from Gaza.

University of Victoria art professor Robert Dalton focused his PhD dissertation on children in warzones and their graphic drawings of what they’ve been exposed to. Dalton has done extensive studies on this topic and how therapeutic drawing can be for children growing up in these circumstances. And, unfortunately, children drawing what they see in times of war is nothing new.

“The first children’s war-torn art I saw was a collection I saw in the ’80s that was gathered by Canadian relief workers at refugee camps in Central America,” he says.

The relief workers handed out art materials to keep children busy. The children tended to draw vivid experiences that had been troubling for them. This helped them address their inner demons and start the path to self-recovery.

“I can’t remember ever being so moved by an exhibition as this body of work by children who had first-hand experiences with civil war, so I began to focus my interests in this area,” says Dalton.

When Dalton did his PhD at Ohio State University, he wanted to see what children’s drawings were like from children who hadn’t experienced war compared to those who had.

“My seven-year-old son, like many other boys that age, was interested in the G.I. Joe phenomenon during his very masculine gender development phase, so I targeted other children his age who were also in that phase,” says Dalton.

The Gulf War began during Dalton’s research; he noticed that because America had troops in war, children changed the style of war drawings they did.

“The pre-Gulf War drawings were very much like a military forces square-off, quite similar to a sporting event,” he says. “After the Gulf War began, the drawings were less about combat but more about ‘USA vs. Iraq’ and ‘we’re going to win,’” he says.

Dalton gives an example of one girl who began drawing about war after the Gulf War began. Her drawings had lots of emotion in them, with people weeping, distraught about the violence of war. She didn’t understand how people could harm each other, so she turned to drawing to deal with her feelings.

“This was a pivotal moment when we realized that the children shifted from drawing about war because of gender identification to drawing as a way to deal with real-world situations,” says Dalton.

After this study, Dalton rallied to get children in the streets of Kabul, Afghanistan ledger paper and art supplies from the Canadian military contingent. They asked the children to draw a world they wanted to live in, and they got results that they hadn’t expected.

“We never asked these kids to relive their horrors, but as it turns out, they couldn’t think ahead until they had already dealt with their present and past,” says Dalton. “As a result, we got some very tragic drawings of violent eyewitness experiences that they had chosen to draw themselves.”

Even though Dalton received surprising results, he decided to show this work so that people could understand how much it was affecting the Afghani children. He toured schools in Victoria with the art and explained that these children couldn’t picture our world, considering that things like playing soccer and flying kites are banned there.

“After the school touring, we started an exchange program, similar to pen pals, where Canadian and Afghan children would send art they created back and forth to each other,” says Dalton. “The Canadian children sent over hopeful pictures, and as a result Afghani children sent back much more joyous pictures with beautiful things like birds and flowers.”

Dalton says it’s important for us to see how children perceive the world because as citizens of the world we should feel a sense of responsibility and recognize that we can do better as adults. Frances Everett, representative for Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East, who are bringing the exhibit to Victoria, agrees with Dalton that this is an important matter for us as Canadians to address.

“The images in A Child’s View from Gaza are graphic,” says Everett, who adds that the situation in Gaza is particularly difficult because the conflict isn’t over. “These children let out a lot of their inner feelings and thoughts through their art therapy. It’s important for people to see how the war is affecting these children, and we hope our exhibit will get people thinking, talking, and researching more into how we can help.”

Camosun College political science instructor Mona Brash is concerned about the effects that war has on children. She says that children are easily influenced and generational beliefs and views can grow stronger the longer these conflicts are not resolved.

“If negative feelings are imprinted in these children’s minds when they are young, then there’s a chance that they will carry these thoughts as they age, and particularly carry thoughts of revenge,” says Brash. “Imagine how this could impact relations between Israel and Palestine when these children are adults and become the decision makers.”

Brash, Everett, and Dalton all agree that the example that’s set for children is imperative to our future, because children’s values are what will determine how we proceed in the world.

“When children make friends and develop a sense of compassion it means well for our future,” says Dalton. “I think we’re living in more enlightened times with mass media and travel. I think the barriers of hostility and misinformation will break down and I hope this collection will play some small role in moving us forward.”

A Child’s View from Gaza

Until December 4 (reception November 15, 7 pm)

A. Wilfrid Johns Gallery (MacLaurin Building, UVic)

events.uvic.ca