The apparent simplicity of flushing a toilet has become a highly complex scenario in the Capital Regional District (CRD).

The CRD has spent millions of dollars, and several years, deciding how to deal with its sewage. Since ordered by the provincial government to start treating sewage in 2006, the CRD and others have undertaken numerous studies by engineers and scientists, and numerous opinions have been formed by politicians and the public.

The CRD is made up of 13 municipalities, seven of which hook up to the main sewage pipes. Today, these municipalities (Victoria, Oak Bay, Saanich, Langford, Colwood, Esquimalt, and View Royal) pump over 130 million litres of sewage effluent into the Strait of Juan de Fuca every day, from Macaulay Point in Esquimalt and Clover Point in Victoria.

Although that seems like a lot, researchers for the CRD says the tidal system and currents in the strait can handle it. The potential harm levels are consistently below their “trigger,” which is when the level of toxins in the effluent starts damaging marine life.

Some environmental groups disagree, and say that the trigger is set so high it’s nearly impossible to reach. In fact, it was the Sierra Legal Defence Fund (now called EcoJustice) who originally brought the CRD’s method of sewage disposal to the attention of the provincial government.

Not in my backyard

Lynda Hundleby, a councillor for the city of Esquimalt, is disappointed with the February 8 decision by the CRD’s liquid waste management committee to put a new secondary treatment plant at McLoughlin Point, which is near the existing plant at Macaulay Point, but wants to make it clear she’s not necessarily speaking on behalf of the city.

The site, which is at the northwest entrance to the Inner Harbour in Esquimalt, is currently owned by Imperial Oil, and generated $51,300 in property taxes for the municipality last year. When the CRD takes over, they will be exempt from municipal taxes.

“It’s difficult for us because we have a very limited tax base,” says Hundleby. “We will not be getting any revenue from that land, and we’ll have to make it up somehow. I’m really unhappy about the fact that we’re not being compensated in any way.”

Hundleby also feels that putting a sewage treatment plant in such a pristine location doesn’t make sense. The plant will likely be visible from the cruise ship dock at Ogden Point, and to anyone coming and going from the harbour.

“Esquimalt is on the record saying we don’t think this is a good use of prime waterfront land,” says Hundleby. “Having said that, maybe there are ways to make it look better, but sounds to me like cost is the overriding factor. They’re not really concerned with what it looks like.”

One reason for choosing McLoughlin Point is the existing infrastructure at Macaulay Point, which is just around the corner.

“The pipes are in the ground going to Macaulay already, which was one of the main reasons we were told this site was chosen,” says Hundleby. “On the one hand, I can understand that, but it’s still a bit unfair for us.”

Hundleby says that Esquimalt was never properly consulted about the McLoughlin Point site. Denise Blackwell, a Langford councillor, CRD director, and chair of the core liquid waste management committee, says they attempted public consultations several times with Esquimalt, but there were scheduling conflicts.

Hundleby feels the lack of consultation might be due to the fact that, hypothetically, the CRD could put the treatment plant anywhere they want within the district, because municipalities don’t have veto power. And, because representation for municipalities is done proportionally by population, Victoria and Saanich have nine votes out of 23 total. Esquimalt, on the other hand, has only one.

“It doesn’t really matter what the rest of us think,” says Hundleby. “The bigger municipalities have control because they can out-vote us.”

Environmental politics

At the Macaulay and Clover Point sites, sewage goes through preliminary screening. It’s sieved through a metal screen with six-millimetre holes, and the effluent is heavily diluted before flowing out over a kilometre offshore.

It’s then released through diffusers, 60 metres below the surface, where it’s dispersed and transported by strong tidal currents.

Also released into the strait is storm water, which is, essentially, anything that passes through the drainage system. The problem with just having preliminary screening in place is substances like fats, engine grease, and detergents make their way into the ocean, and can have adverse effects on marine life.

John Bergbusch has an extensive background in municipal politics. He’s also the chair of ARESST, a group of residents who believe the current system works, and the McLoughlin Point treatment plant is a mistake.

“It’s the wrong proposal,” says Bergbusch. “There’s things [the CRD] could do to fix the environment, like improve the storm drains, and enhance the source control program, but the project that they are working on is the wrong program at a cost of $800 million.”

Bergbusch says the CRD hasn’t done adequate research. However, Jack Hull, the CRD Integrated Water Services general manager, says they looked at multiple options, including a scenario with several smaller treatment plants throughout the region.

“I can’t think of anything we didn’t look at,” says Hull. “What was common with all of the options we looked at was McLoughlin.”

CRD director Blackwell seconds Hull.

“We’ve spent $10 million on studies in the last few years,” she says. “I’d say that’s plenty of research.”

According to members of ARESST, more should have been done to promote the unique environment in the Juan de Fuca Strait to the provincial government. The CRD has been conducting its own research in the strait to monitor the marine environment for years. Bergbusch doesn’t understand why they didn’t make a stronger case for the current method when they had the chance.

“The CRD’s own research always shows the marine environment around the diffusers to be doing very well,” says Bergbusch. “What is the reason for going ahead with [the treatment plant], other than, perhaps, a public relations effort? One of the reasons we object is they haven’t given us a good reason to move ahead.”

However, the reason given by Hull is simple: the province issued an order, and it wasn’t up for discussion. Beyond that, he says, the federal government is moving ahead with legislation regarding sewage treatment.

“They’re supposed to be announcing it in March,” says Hull, “with a requirement for secondary treatment by 2020.”

Regardless of this, says Bergbusch, the grounds for a treatment plant are weak.

“It’s not in the environmental interest, it’s certainly not a green project, and it’s a waste of money,” he says.

Antiquated technology?

Dave Saunders, the exiting mayor of Colwood, is an outspoken critic of the CRD’s sewage treatment agenda. He, too, feels that there wasn’t adequate research done by the CRD, and that they’re not thinking outside the box when it comes to technology.

“In this day and age, when we’re presented with so much new technology, I feel that the CRD should have done a better job of exploring all the other opportunities out there,” says Saunders.

Hull says the design for the secondary treatment plant hasn’t been decided on, and they will be accepting proposals from the private sector, although they won’t be taking any risks. As it stands, sewage will be pumped to McLoughlin Point for primary screening, and the sludge will be piped to Hartland Landfill in Saanich for secondary treatment.

“We’re not going to put in any experimental technology when there’s no guarantee at the end of the day that it will work,” says Hull. “It’s got to be proven technology that, when completed, will function as designed.”

The CRD will be looking for things like cost-effectiveness and energy use in the new design, but Saunders maintains they are relying on outdated mechanical engineering methods to make their decisions. He says even the idea of primary and secondary treatment needs to be revisited.

“When I was mayor, I had some people saying they could do the sewage treatment model for no cost to the citizens in the area, because they treat the sewage as a resource,” says Saunders. “For that to work there should be no separation of solid and liquid waste, but that’s what the plan is right now.”

Besides the technological aspect of the McLoughlin Point plant, Saunders is concerned with its location for ecological reasons.

According to the Natural Resources Canada website, McLoughlin Point is in the “intermediate risk zone” in the case of a tsunami. For Saunders, this is reason enough to discount McLoughlin Point as an option for sewage treatment.

“It makes no sense to put that kind of infrastructure in a single spot that is at such a high risk,” he says. “There is no emergency backup with this plan.”

The cost of rapid growth

The most recent census data shows that Langford is the fastest growing city in the province. In the last five years its population has increased by 30 percent, to just under 30,000, and is projected to double in the next decade.

While Langford enjoys the benefits of development, the population has grown faster than some of our shared infrastructure, like highways and sewers. This has lead to a lot of frustration for commuters and taxpayers, who now must suffer the burden of unforeseen growth.

According to the CRD, the cost estimate for the new wastewater management facilities is $780 million, although infrastructure projects are known to run over budget.

The provincial and federal government have said they will each pay for a third of the cost, with the seven core municipalities paying for the rest, but the CRD is still waiting for the funding to be guaranteed in writing. Official numbers aren’t available, but it will certainly mean increased taxes for homeowners in the seven core municipalities.

The rapid growth also affects the future of sewage treatment. At the current rate of growth, the McLoughlin Point plant will only be able to serve the regional population until about 2035. Hull estimates the plant will be up and running by 2018, which means our infrastructure investment will potentially be obsolete in 20 or so years.

Opponents of the McLoughlin Point sewage treatment plant say for the near billion-dollar price tag this just isn’t good enough, given the issue of inadequate infrastructure that we’re dealing with now.

“Why these generally clever people insist on forging ahead with this project is a mystery to me,” says Bergbusch.

Blackwell maintains they don’t have a choice in the matter.

“We were ordered to do treatment by the provincial government,” she says. “Even if we hadn’t been ordered to do it by the province, the new federal regulations mean we would have to do it anyway.”

Your story is misleading, omits important facts, and is incorrect or inaccurate in its interpretation of facts presented – the only pro-sewage plant source not quoted was Mr Floatie! Your misunderstanding starts with headline, and if you were seeking to use some alliteration, you could have chosen a more accurate headline such as “Our Sustainable Sewage System: Economical and Environmental”!

1. The CRD already has several land-based secondary-stage sewage treatment plants, but the “core area” marine-based sewage treatment system was approved more than 30 years ago and has operated sustainably as studies have shown that it is the most cost-efficient system, with few, insignificant environmental impacts, and has been successful because of the combination of a vigorous CRD source control system of effluent quality together with the two long screened outfalls and constant monitoring. Certainly the CRD has not forgotten this marine-based sewage treatment system!

2. Many oceanographers, biologists, engineers, economists and public health doctors have published their names attached to their approval of the current marine-based sewage treatment system. A letter published in the refereed journal Marine Pollution Bulletin by oceanographer Dr Peter Chapman is but of these public documents and includes the public approval of several scientists. Some are members of ARESST, some speak independently – and Dr. Shaun Peck, who was Victoria’s public health chief for several years, created Responsible Sewage Treatment Victoria, where dozens of documents that discuss our system are linked for downloading.

3. Be aware that this billion-dollar sewage plant project has gotten so far without any legal challenge by the CRD, not any environmental impact assessment under BC’s Environmental Assessment Act, because BC allows sewage plants to be built with only the guidelines of the totally-inadequate Municipal Sewage Regulations. The land-based plant will not be compared to our current marine-treatment system at all, but can proceed without public consultation (the reason for Councillor Hundleby’s concern). We don’t yet absolutely know for certain what marine environmental impacts will be either alleviated or created by this land-based sewage plant, but its quite certain that the under-harbour pipeline will cross a seismic fault, and the plant location is under an unofficial flight path use by many floatplanes.

4. Our current marine-based sewage treatment system doesn’t just follow the adage, “the solution to pollution is dilution,” but rather the scientists have seen that the effluent is broken-down into stable chemical compounds that pose no measurable threat to marine life. Unfortunately, the legal regulations do not recognize Victoria’s unique marine environmental situation and do not actually measure the environmental impact of our site. The current issue of recent mussel-population reduction around Macaulay outfall could well be due to climate change impacts and have nothing to do with the outfall as such. Certainly, UBC zoologist Chris Harley supports that thesis and is actively researching it.

5. Many of the “studies” that the CRD has spent so much on are not directly related to our CRD sewage system, but rather to untested and speculative options that have been favourites of some of the CRD directors on the sewage committee. For example, unworkable options like urine-separation toilet schemes have been considered by CRD engineers and consultants, and including wasted money micro-resource recovery sewage plants to be dotted around the region. What they haven’t studied is either a legal challenge to the provincial dictate demanding a land-based sewage plant, or making a serious comparison to our current marine-based sewage treatment system.

6. You chose to end your story with Director Blackwell’s defeatist comment that the feds made us to it. Rubbish! The CRD has totally neglected its due-diligence by not investigating a legal challenge to the provincial or federal dictate. She is hiding behind politicized Liberal provincial and Harper federal policies that need to be challenged. Progressives challenge Christy Clark and Harper. Just like many of us object and fight against Harper’s Bill C-30, we need to fight against unsustainable policies that will fail to deliver any measurable environmental improvements.

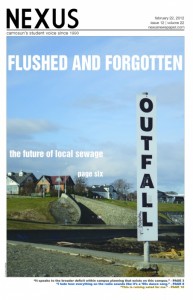

7. Your cover photo will tend to leave casual viewers who don’t read the text carefully with the impression that the mouth of the outfall is right at the shoreline, when (as noted buried far down in story) it is really far offshore and deep underwater. Rather than emphasizing the sign, better to emphasize the subtle architectural and functional beauty of the Clover Point pump station that you have almost hidden in the background of the cover photo. This is a common mistake in news photos – but not as bad as a Times Colonist municipal election story whose photo confused sanitary sewers with totally-separate issue (and much worse than our sanitary sewers) of storm sewers!

8. Most importantly, the common-paradigm repeated by your story ignores most of the environmental negatives of a land-based sewage treatment plant and its associated works, such as the pipelines taking sewage sludge 20 kms up to Hartland landfill for processing. Our current system produces NO sewage sludge (its 99.7% plain water), and very little greenhouse gases – but a land-based treatment system produces thousands of tonnes each each year of both these noxious problems.

9. The Eco-Justice lawyers were not looking at environmental impacts, but only at the unreasonable application of regulations that had been promulgated for other environments – not our own. When environmentalists decided to “prove” that our outfall effluent was harming salmon with a bogus “test”, they lowered a cage of trout right over the outfall mouth – and sure enough, a few minutes later, the fish died. Why use fresh water fish in a saline environment? And dead fish aren’t piling up at the outfall because fish are smart enough to know that if they don’t like the effluent right there, they can just swim a metre away, and oxygenation is fine.